“In today’s academic publishing circus, ‘service’ and ‘free contributions’ are just sleazy terms for fleecing scholars in the name of altruism.”

Lanfranco Aceti

ABSTRACT

This essay critically examines the costs associated with operating within the realm of academic publishing, particularly focusing on the concepts of “free contribution” and “service to the academic community.” These terms have increasingly come to symbolize a form of neo-serfdom within a context where non-profit academic publishing and academia have evolved into exploitative corporate entities.

The traditional frameworks of service and support within academic communities have been redefined into institutionalized, unreasonable demands within a transactional educational model. This model positions students as consumers on one side and universities and publishers as corporate entities on the other. This paradigm effectively excludes artists, professors, authors, editors, and reviewers from receiving appropriate monetary compensation for their contributions, which are often provided gratuitously to the publishing industry and academic institutions.

In this context, how does a publication navigate the interstices of these exploitative processes? What ethical responsibilities do corporate publishers have in maintaining “free” content as Open Access (OA), while simultaneously promoting visibility for fields like art and humanities—disciplines that continually struggle with funding and recognition? Can one achieve both acknowledgment and monetary compensation without succumbing to institutional disdain and neglect?

LEA (Leonardo Electronic Almanac) serves as a case study in this discussion. As a publication entirely managed by volunteers, LEA grappled with increasing demands from an audience expecting a high standard of service without contributing financially or otherwise. Despite the rising expectations, there has been a lack of support or compensation for the volunteers who uphold the publication’s mission of preserving and advancing the history of art, through both aesthetic endeavors and academic discourse, which might otherwise be marginalized or lost.

KEYWORDS: Exploitation, Academia, Publishing, Free Contribution, Art, Open Access

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Professor Stephen Wilson, former Editor in Chief of the Leonardo Electronic Almanac. His guidance was invaluable, and he generously offered his mentorship without charge, even while he was bravely battling cancer.

His support and wisdom have profoundly influenced this work.

Introduction: Should We Have Been All Plumbers?

This essay stems from over a decade of volunteer work with Leonardo/ISAST – MIT Press, where I have served as Editor-in-Chief of the Leonardo Electronic Almanac (LEA). The impetus for this piece was sparked by a broader conversation on the nature of volunteer labor, which emerged during my efforts to establish an academic exchange program between institutions in Europe and the United States. My objective was to facilitate a short-term academic opportunity for one or two European students, enabling them to volunteer for a period of two months at a European university during my visiting professorship. The intention was for this experience to serve as a stepping stone toward future employment opportunities in the United States, provided that sufficient financial backing could be secured and the intricate bureaucratic processes between U.S. and European academic institutions successfully navigated. However, this initiative faced additional challenges due to the prohibitive costs and complexities of securing a U.S. visa for European students pursuing year-long research internships.

The proposed framework aimed to achieve several objectives: a) to initiate an academic exchange that could expand over time; b) to effectively navigate the complexities of institutional bureaucracies in both Europe and the U.S.; and c) to allow sufficient time for securing research funding and fostering collaborative relationships among leading global institutions.

Despite these intentions, the public announcement of this volunteer opportunity—shared by a colleague on an online platform in an effort to maximize visibility within the student body—was met with criticism from two students, highlighting broader concerns about the role of unpaid labor in academia. Their critiques, while focused on important systemic issues, ultimately led to to the premature termination of the initiative. This setback underscored the ongoing challenges faced by LEA, a publication that has long relied on the voluntary contributions of academics. The sustained efforts of scholars, who generously offer their time, expertise, and networks, have enabled LEA to thrive and serve as a critical platform for interdisciplinary scholarly and artistic engagement. Despite these ongoing difficulties, LEA has consistently provided a valuable platform for both established and emerging scholars, offering a space for rigorous scholarly and artistic engagement in an interdisciplinary field. Importantly, it has maintained this commitment to fostering new voices in the arts and humanities without imposing financial barriers, reinforcing its role as an accessible and inclusive resource for the academic community.

What I had initially resisted, and perhaps overlooked, was the unsettling reality that a new generation, shaped by the very neoliberal policies they profess to critique, often seems content to operate within an exploitative system—as long as their voices of dissent can be heard. This paradox reveals a deeper complicity in the structures they oppose, where critique is permitted but rarely paired with tangible, systemic action.

This experience highlighted my own evolving role within such frameworks—not necessarily to dismantle established systems entirely, but rather to navigate, adapt, and subtly reshape them. By carving out spaces within these institutions, I have sought to enable “disruptors” to operate within alternative, if constrained, models of engagement.

In this light, it becomes essential to critically interrogate the definitions of “university” or “non-profit publisher.” What values do these institutions claim to uphold? Who is their intended audience? And, more importantly, what policies do they implement to meet the evolving demands of that audience?

One cannot ignore the broader shift in higher education, as it increasingly reflects neoliberal agendas. As one scholar aptly notes, “[i]t expresses the policies of neoliberalism, repealing the policies of the New Deal and Great Society, shifting the university from being a public entitlement like high school to more of a pay-as-you-go, privatized service.” [1] This commodification of education, driven by market forces, necessitates a reevaluation of our participation in these structures.

A problem often serves as a catalyst for reflection, and in this instance, it became evident that the issues at hand were not only systemic but also deeply intertwined with my persistent efforts to foster a collaborative process aimed at long-term goals. Both parties—the exploiters and the exploited—seemed willing to operate within the restrictive confines of neoliberal policies, content to maintain a status quo that prioritized short-term individual gains over collective, long-term progress.

I was forced to confront the disheartening reality that the academic system, along with its participants, increasingly values personal advancement over the cultivation of collegiality, shared commitment, and collective interests. The enthusiasm for genuine interdisciplinary collaboration has waned, replaced by an expectation that individuals exploit these synergies primarily for their own benefit, even if doing so risks undermining the very foundations of the enterprise.

This realization was the source of my deep frustration—an irritation I might downplay with the veneer of British understatement, but which is in fact rooted in my years of unpaid labor for LEA (Leonardo/ISAST – MIT Press). To quantify this service, Glassdoor estimates for comparable editorial leadership positions suggest that my median annual salary would have been $85,601, with a lower range of $52,000 and an upper range reaching $120,000.[1] The disconnect between the voluntary nature of my contributions and the potential compensation underscores the systemic undervaluing of intellectual and cultural labor, an issue that extends far beyond my individual experience.

The time, effort, and resources I have dedicated to reviving and sustaining LEA represent a significant financial value. This includes approximately $10,000 annually for travel and accommodation related to editorial meetings, conferences, and other engagements essential to the publication’s operations.

Over the course of a decade, my voluntary work can be conservatively valued between $520,000 and $856,010, a figure that excludes the additional $100,000 spent on travel and accommodation. This total reflects my contribution to the broader academic “community” during this period. Moreover, factoring in the countless hours I dedicated beyond a standard workweek—often on weekends, holidays, and during periods when European labor laws would have mandated overtime compensation—the true value of my contributions climbs even higher. For the purposes of this analysis, I will retain the higher estimate of $856,010. This figure underscores not only the extraordinary monetary value but also the immense time commitment involved, which amounted to the equivalent of a second full-time job.

Had I been compensated for my efforts, the amount would have sufficed to purchase a luxury vehicle, such as a Porsche, highlighting the staggering personal financial cost that I absorbed. This substantial sum represents a burden that the academic and publishing industries have largely evaded while benefiting from the work I contributed freely. Despite these realities, my contributions have played a pivotal role in advancing interdisciplinary arts scholarship, fostering new research, and creating opportunities for emerging voices in the field.

Consider, for comparison, that “some plumbers charge a flat-rate service call plus an hourly rate for their labor. The plumber may be able to break down their labor rate into quarter-hours. The average hourly rate ranges from $45 to $150.” [2] This stark contrast serves to highlight the undervaluation of intellectual labor in academia, where scholars invest years of expertise and uncompensated time to sustain projects like LEA.

The financial realities of running a journal, particularly one reliant on voluntary labor, have made it imperative for me to restructure LEA and clearly communicate these conditions to our contributors and the broader academic community. In an era where neoliberal corporate entities, often masquerading as non-profits, perpetuate the exploitation of scholars in the humanities, transparency is no longer an option—it is a necessity.

This essay seeks to provide a detailed account of the operational dynamics underpinning LEA, offering insight into the rationale behind its restructuring. It is intended as both a critical reflection and a practical guide for current and future contributors, outlining what they can expect when engaging with LEA and how to navigate their involvement with full awareness of the financial and systemic realities they face.

The structural shift at LEA marks a deliberate move towards fostering a new approach to academic publishing, one that actively challenges the exploitative dynamics that are endemic to both academia and the publishing industry. It is an editorial experiment in exploring post-capitalistic models of publication, searching for methods that might circumvent—or at the very least mitigate—the inherent exploitation within the current system, should such methods be possible. This endeavor represents a fundamental attempt to rethink the intersection of scholarship, labor, and publishing in ways that foreground fairness, sustainability, and intellectual autonomy.

“As of 2015, the academic publishing market that Elsevier leads has an annual revenue of $25.2 billion. According to its 2013 financials Elsevier had a higher percentage of profit than Apple, Inc.” [3] This data underscores the glaring disparity between the immense profitability of major academic publishers and the undervaluation of scholarly labor, particularly in the humanities, where contributions are often expected to be made without financial compensation.

In response to this inequity, I have decided that, beginning in January 2019, LEA will implement a standardized rate of compensation for all individuals involved in the production of articles or publications. Drawing a direct comparison to labor sectors outside of academia, I have adopted a median hourly rate of $100—equivalent to that of skilled tradespeople such as plumbers. This policy will be applied to all new projects and initiatives undertaken by LEA moving forward, ensuring that contributors are fairly compensated for their intellectual and creative labor.

This shift not only marks a turning point in LEA’s operational model but also serves as a broader critique of the exploitative dynamics pervasive in the academic publishing industry. By instituting fair wages, LEA aims to set a precedent for alternative models of publication that prioritize ethical labor practices and recognize the value of scholarly contributions in a way that traditional academic publishing has consistently failed to do. [4]

Reimagining Fair Labor: The Cost of Passion vs. Professionalism

To address exploitation, it is essential to comprehend the financial dynamics that underpin academic publishing. What does it mean to compensate everyone involved, and is it truly feasible in a landscape that has long relied on voluntary labor?

There are two primary approaches to exchange in this context: a) one that involves monetary compensation and b) one rooted in personal passion, wherein labor is freely given. The latter has been a prevailing model in the humanities, where academic goodwill often substitutes for fair remuneration. However, it is fundamentally untenable to maintain a framework of free exchange while simultaneously demanding the level of service expected in paid contractual environments. In such a system, contributors are left in a contradictory position—acting as customers who are expected to deliver a service without receiving financial compensation in return. [5]

This incongruence reveals a larger issue within academic and non-profit publishing. For years, scholars have been asked to contribute their expertise, time, and networks under the guise of collegial collaboration. Yet, this framework masks an exploitative model that benefits institutions far more than the individual contributors.

To address this imbalance, beginning January 1, 2019—coinciding with the ten-year anniversary of my tenure at LEA—there will be two distinct options for engagement.

Option 1: Work = Money

The first option, termed “Work = Money,” establishes a clear, paid contractual framework to address accusations of exploitation within academic publishing. Under this model, each individual involved in producing an essay or volume will receive financial compensation. Specifically, authors and their affiliated institutions will be required to provide financial support amounting to $4,200 per essay submitted to LEA.

This financial structure formalizes the relationship between authors and editors, ensuring that editors are paid $1,000 for their labor while also compensating all other personnel involved in the production process. Importantly, this arrangement positions authors as customers, guaranteeing them the right to expect timely delivery and adherence to deadlines. However, this model also imposes clear limits on what can reasonably be demanded. Unpaid editorial labor, such as requests for extensive revisions, will no longer be tolerated without corresponding financial compensation. Editorial work will be strictly regulated by predefined time allocations, with additional costs billed in advance for articles requiring significant rewrites. This ensures that the process remains equitable, efficient, and manageable for all parties involved.

LEA’s commitment to fair compensation extends beyond editors to the entire peer review process. Unlike many contemporary journals, LEA will pay all three blind reviewers (selected by the publication) and two friendly reviewers (suggested by the author). This system not only provides equitable compensation but also fosters a more robust and engaged critique. Authors will benefit from the involvement of reviewers familiar with their work, while also receiving insights from external, impartial experts. This stands in contrast to the increasingly superficial feedback often observed in contemporary peer review practices. [6]

Moreover, LEA will introduce a standardized hourly rate for all types of labor, from editorial work to marketing and administration. Whether contributors are students or seasoned professionals, they will receive fair pay for their contributions, aligning with LEA’s commitment to equity and fairness amidst widening disparities in academic labor. By implementing this structure, LEA seeks to disrupt traditional publishing models that rely on unpaid or undercompensated labor, creating a more sustainable and ethical framework.

This system also promotes a culture of accountability among staff and volunteers. Compensation will be directly tied to work completed: those who fail to fulfill their responsibilities will not receive payment, credit, or references. This policy addresses issues with volunteers who may abandon their responsibilities after training or produce substandard work while demanding disproportionate recognition.

Option 2: Volunteer or Go

The second approach, titled “Volunteer or Go,” is predicated on the principle of voluntary labor, recognizing time as an invaluable, non-recoverable resource. In this model, those who choose to contribute their time freely—whether as editors, reviewers, or contributors—are not merely volunteers but essential stakeholders in the publishing process. The value of this contribution cannot be overstated, and thus, a culture of respect and courtesy is not just encouraged but mandated. The time and effort donated by these individuals deserve recognition and should be met with the highest professional regard.

Under the “Volunteer or Go” framework, contributors who lack the financial means to support their essays or volumes are required to contribute in other meaningful ways. They are expected to offer time, labor, or other opportunities that advance the publication’s mission. These contributors must demonstrate to both the editorial team and the Editor-in-Chief the value of their work, emphasizing how their proposed project will enhance the goals and visibility of LEA.

This model emphasizes that although financial support may not be available, the willingness to invest time and labor is an equally valid currency. Authors who opt for this pathway must engage with the editorial process fully, adhering to deadlines, actively promoting the resulting work, and offering support to their peers. Whether through publicizing essays or participating in scholarly events, contributors help foster a cooperative and mutually supportive academic environment. The underlying principle here is not transactional but collaborative: collective effort enables the realization of high-quality scholarship within the existing frameworks of academic publishing.

By prioritizing shared labor and reciprocal contribution, the “Volunteer or Go” option sustains a communal, non-monetary approach to scholarly production. It honors the voluntary ethos while providing contributors with a clear structure that avoids the exploitative nature of many contemporary academic publishing models.

These two distinct models—“Work = Money” and “Volunteer or Go”—both offer clear advantages and potential drawbacks. Together, they widen access to LEA for a diverse array of scholars and practitioners, enabling the publication of valuable and innovative work without necessarily imposing financial strain. Both pathways uphold the principles of fairness, equity, and respect for intellectual labor, ensuring that contributors are either fairly compensated or recognized for their voluntary commitment.

The table below provides a transparent breakdown of the costs associated with publishing each essay, ensuring that contributors understand the financial requirements and that all published work remains open access. For multi-essay volumes, the overall costs are calculated by multiplying the per-essay cost by the number of essays included, ensuring clarity and transparency throughout the editorial and publishing process.

| Roles | Allocated Hours | Price per hour | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Editor 1 | 3 hours | $100 | = | $300 |

| Editor 2 | 3 hours | $100 | = | $300 |

| Editor 3 | 3 hours | $100 | = | $300 |

| Reviewer 1 | 2 hours | $100 | = | $200 |

| Reviewer 2 | 2 hours | $100 | = | $200 |

| Reviewer 3 | 2 hours | $100 | = | $200 |

| Reviewer 4 | 2 hours | C$100 | = | $200 |

| Reviewer 5 | 2 hours | $100 | = | $200 |

| Designer | 3 hours | $100 | = | $300 |

| Mktg & Mgmt | 5 hours | $100 | = | $500 |

| Administrator | 5 hours | $100 | = | $500 |

| GRAND TOTAL | $3200 | |||

| +VAT |

The table provided outlines the comprehensive production costs per essay, excluding payment to the author. Addressing the issue of author compensation, however, requires a more intricate approach. After careful reflection, I have opted, in my capacity as Editor-in-Chief of LEA, to recommend that authors request a payment of $1,000 plus VAT from their home institutions for their writing. This figure is marginally lower than the amount I was personally compensated for publications in international academic journals during my tenure at Sabancı University, Istanbul. Consequently, the total cost for publishing an essay, inclusive of the author’s fee, would reach approximately $4,200 plus VAT per essay.

Ideally, the burden of compensating authors should be shared between universities and publishers. However, in today’s academic climate, where scholars are overwhelmed by administrative duties, teaching loads, research commitments, and various service roles, the economic realities are stark. Both universities and publishers derive immense benefit from the unpaid writing of scholars—a striking contrast to the meager financial resources available to journals like LEA, particularly those operating in the humanities.

The challenge of fairly compensating authors is symptomatic of broader systemic issues within academic publishing, and addressing it meaningfully remains elusive. Nevertheless, to underscore the exploitative nature of this framework, and the broader abuses faced by cultural producers in the humanities, LEA will institute a policy requiring authors to either request this fee or submit a formal letter from their department chair. This letter must state:

“The university is unwilling to pay the author, and the author consents to waive the associated fee, thus holding LEA harmless for the exploitative nature of these frameworks and processes.”

While I acknowledge that this policy serves merely as a palliative, it is my hope that it will provoke internal conversations within academic departments regarding the value of research and writing. By documenting each instance where a university refuses to compensate its scholars, LEA can compile an archive of the pervasive exploitation within twenty-first-century academia. Over time, these letters may be assembled into a dedicated LEA volume, serving as a historical testament to the systemic issues plaguing academic and editorial labor in our era. Such a collection would offer future scholars critical insights into the precarious conditions under which intellectual work in the humanities continues to unfold.

The mathematics are simple: $3,200 plus VAT per article multiplied by 100 essays equals $320,000. This figure represents the monetary value of producing 100 articles. Given LEA’s publication history, with 266 articles over a decade, the financial value becomes even more staggering.

$3,200 per article x 266 articles = $851,200.

This sum reflects the cumulative monetary cost or value—strictly in financial terms—of what LEA has produced over the past ten years, based on these calculations.

If LEA’s contributors had been paid for their work, and had we collected payment for our editorial labor, including my own salary as Editor-in-Chief, we would be looking at a total of $851,200 + $856,010 (the latter sum representing the unpaid salaries) amounting to $1,707,210.

To contextualize these figures, consider this: the Porsche 918 Spyder pictured below is priced at $845,000. Thus, with the money LEA was meant to pay its contributors—or with my own deferred salary—we could easily afford at least one of these Porsches. In fact, if everyone involved had been properly compensated, we could buy two of these high-performance cars and still have enough left over to celebrate.

Image 1. Lanfranco Aceti, What You Owe Me, 2018. Meme. Dimensions: variable. Credit: VIP Motors – https://vipmotors.ae

The choice of a Porsche as a comparative metric in this discussion is not coincidental. It stems from two emails I received in response to my proposal for a two months unpaid internship, which raised several critical points. First, these responses revealed that I may not have adequately clarified the goals and expectations of the internship. Second, they prompted me to reevaluate the ethical underpinnings of my approach.

My aim was to open doors, provide access, and create opportunities—an ambition shaped by my own extensive experience volunteering to build my career. However, I did not fully grasp how expectations have evolved, and how the conditions and demands facing emerging professionals have grown more complex. While my demands as a young scholar were focused on securing access to resources and proving my capabilities, in a context in which volunteering was the only way upwards for someone without connections, today’s expectations have shifted. They now center on time, labor, financial compensation, and personal fulfillment.

This shift reflects a broader transformation in academic and professional priorities. Where self-investment and professional growth were once paramount, today’s post-postmodern landscape increasingly emphasizes minimizing labor while maximizing financial reward and personal satisfaction. The equation has evolved from one of proving oneself through unpaid or underpaid labor to one where satisfaction and remuneration are paramount, to those within privileged communities who can afford it, and access alone is no longer sufficient compensation for time and expertise.

“Mr. Aceti have a warm welcome in [our city and our university].

I dont know exactly your expacations about [our country], [our country’s] Students and programmers when it comes to their social and economic situation, but maybe you should lower them a bit. Most of the people here (still) deal with inherent necessities of capitalism which means: You need to SELL labor to buy food and pay your monthly rent. We live neither from air nor love, food is not for free and cannot be picked from trees. I guess you know that. Why should ANY programmer work for free? What do you think a craftsman is doing after you tell him he should do some renovationwork at your house for free? Right, he will pack his gear and leave. Why should artists and creatives should react differently?

Thats worse than feudalism! programmers would may get no money but a place to sleep and at least a warm meal per day. Here I get nothing.

If you have no budget to pay proper wages you should also have no intern. (Same reason I have no Porsche. Because I have no money for that. No money no funny. Very easy)

Have a nice day,

[signed, which I appreciated very much and was grateful for]

PS: your homepage says you are known for your SOCIAL ACTIVISM. haha. great.”

In many respects, the demand for fair compensation is not only justified but necessary, particularly when critiquing the exploitative nature of current corporate-state capitalist frameworks. However, the email addressed to me revealed several layers of misunderstanding. While there was some merit to the complaint, the writer’s lack of insight and misguided assumptions posed significant issues. These problems seem symptomatic of a broader societal climate marked by a Kantian a priori of self-righteousness, where complexity is reduced to simplistic binaries and ignorance cloaks itself in moral superiority.

The writer’s approach was not a dialogue about the potential merits of the unpaid internship but rather an indictment of the messenger. This response, while all too common, emerges from a wellspring of frustration, anger, and disenchantment—sentiments I deeply understand, having confronted similar challenges myself. However, I have always endeavored to channel my frustration into constructive critique, not always succeeding, avoiding personal attacks in favor of systemic critique. My aim has been to seek common ground before engaging in direct confrontation, maintaining a focus on resolving institutional problems to allow access rather than fixating on individual shortcomings.

In light of this criticism, which gave me pause for reflection, I have chosen to reevaluate the operational framework of LEA. From January 2019 moving forward, I will ensure that all contributors—whether authors, editors, administrators, or volunteers—are fairly compensated for their labor. Justice and equality must be applied uniformly, without exception.

The revised framework will offer formal contractual agreements for those who seek structured compensation, ensuring that every contributor is remunerated according to their contributions. Alternatively, for volumes that are produced through purely voluntary collaboration, participants will engage in a cooperative effort. In these instances, authors, editors, and volunteers will work together without financial remuneration, relying instead on shared commitments to bring the project to life.

A Lesson to Be Taught and One to Be Learned

As I reflected on the two emails I had received, I recognized two distinct strands running through them: first, a palpable anger at perceived exploitation—an emotion I am all too familiar with, shared by countless editors who find themselves burdened with the total rewrites of papers from authors who seemingly care little about their own scholarship, expecting others to shoulder the labor. The second strand was a pronounced hostility toward anyone who does not share the same worldview. In this particular instance, the anger was directed at me for offering an unpaid internship, a proposal that was misconstrued without any attempt at understanding my intentions. The critique, while touching on important points about the realities of capitalism and labor, bypassed a crucial opportunity for dialogue. Had there been an effort to engage constructively, the result could have been something far more productive than a litany of accusations.

Image 2. Lanfranco Aceti, Me!… Me!… aka The Apotheosis of Idiocy, 2018. Meme with “The Simpsons Movie Angry Mob.” Dimensions: variable. From: topsimages.com, accessed September 10, 2018, https://www.topsimages.com/images/the-simpsons-movie-angry-mob-a8.html.aption.

I have always found communities to be deeply problematic. I am not much of a joiner, and I doubt I will ever resolve my negative associations with the concept of “community.” These issues have only compounded over the years, shaped by both personal experiences and broader societal conditions. Communities, in my view, are dangerous loci of power, prone to creating a false sense of commonality that stifles individual thought and divergent opinions. Thinkers like Franz Kafka, George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Giuseppe Verga, Grazia Deledda, and Luigi Pirandello have long articulated similar fears, warning us of the dangers inherent in groupthink, homogeneity, and the totalitarian tendencies of community.

In its most extreme form, the collapse of the state and any return to civility often occurs through the fascistic violence of the community, which, enshrined in a super-community, overtakes all other groups and ways of thinking. The drive to create a “common destiny,” a “common history,” and a “common identity” inevitably results in the suppression of dissenting or divergent perspectives. Corporate identity, much like the academic culture that has appropriated its methods of control, operates within the same fascistic logic. What masquerades as a communal or corporate ethos often reduces individuals to mere cogs within a rigid hierarchy, enforcing conformity under the guise of unity.

The email I received fits into this broader narrative: an assumption that my actions were not only wrong but emblematic of a more systemic problem. What was missing from this critique, however, was a genuine attempt to engage with what I sought to accomplish through the internship—a program that was not just about free labor but about providing opportunities for individuals to gain experience and exposure in a field where such access is notoriously difficult to come by. In my efforts to open doors, to offer opportunities that I myself fought for and worked without compensation to achieve, I did not communicate the underlining frameworks of my intentions. Also, since the international collaboration was in a development phase heading towards a final agreement, it wouldn’t have been professional towards the partners to publicly announce opportunities that were in the process of being developed and agreed upon. The critique I received ignored that context, focusing instead on an assumption that my offer was inherently exploitative.

Perhaps I should have been more transparent, more careful with the shifting expectations and realities of contemporary labor. The expectations I faced when building my career were centered on gaining access to resources, demonstrating my capabilities, and, yes, sometimes working without immediate financial compensation. I recognize that today’s demands are different, and they should be. Compensation for labor is a rightful expectation, especially when considering the economic realities so eloquently expressed by my critic. Yet the refusal to even attempt a conversation, the immediate leap to condemnation, speaks to a deeper societal issue—one that mirrors the very dangers of community that I have long observed. We now live in an age where any divergence from the “accepted” norms is met with hostility rather than discussion.

The challenge, then, is to find a way forward—a method of reconciling the need for fair compensation with the necessity of building opportunities for those who might otherwise be excluded. It is not enough to simply demand wages; we must also ask how those wages can be afforded in systems that are already stretched to their limits. In the case of LEA, for example, there simply aren’t the financial resources to pay everyone for every contribution. This is the reality of academic publishing, particularly in the humanities, where funding is scarce and the burden of volunteer labor often falls on a handful of committed individuals.

Moving forward, I have decided to revise LEA’s operational framework to ensure that all contributors are compensated for their time, where formal contractual agreements are sought. This is not just a response to the criticism I received but a reflection of my broader commitment to fairness. True justice and equality must be applied uniformly, and I will work to ensure that every contributor, whether they are an author, editor, editor in chief, or administrator, is fairly compensated for their labor.

At the same time, we must also recognize that not every project can operate within this framework. For some volumes, collaboration will remain voluntary, driven by the shared desire to create something meaningful without the expectation of financial reward. In these instances, contributors—whether authors, editors, or volunteers—will work together on a cooperative basis, understanding that their efforts are part of a larger intellectual and creative pursuit, not just a financial transaction.

In closing, the lessons learned from this experience are twofold. First, there is an undeniable need to be more explicit and transparent in how opportunities are presented, ensuring that expectations are clear from the outset. Second, there is a need for more empathy and openness in how we respond to perceived slights or injustices. Anger and frustration are understandable, but they should not preclude dialogue. Only through conversation can we begin to address the systemic issues that underlie so much of the dissatisfaction felt by workers today—whether they are academics, creatives, or programmers. Only by working together, by acknowledging the realities on all sides, can we begin to construct systems that are not exploitative but mutually beneficial.

The Erosion of Difference in Contemporary Discourse

The idea that we are not all the same, that we do not share the same values, and that we possess different modes of operation and thought processes seems to be disappearing from public discourse. The self has become the principal or even sole parameter of engagement, erasing the possibility of meaningful difference. In this context, interactions devolve into the assertion of individual perspectives at the expense of true dialogue. The complexity of the “other,” once considered essential to any meaningful exchange of ideas, is reduced to a mirror of the self, a reflection of one’s own beliefs, desires, and grievances. This reduction limits the potential for genuine intellectual growth, as difference is not merely disallowed but systematically erased.

These two emails, while initially perceived as critiques, offered me the chance to reflect deeply on these issues, reconsidering not only the structure of LEA but also my own ethical, social, and personal thinking. What values are we propagating as individuals, educators, and participants in academic institutions? Are we, in our own way, contributing to the fascistic structures that dominate this system? How can we implement radical change, and how do we generate true alternatives? These are the questions that arose in my mind, not merely because of the content of the criticism I received but as a result of its deeper implications for the future of academia, labor, and intellectual integrity.

The Critique of Criticism

The two emails I received undoubtedly had a positive impact on my personal reflections and on the restructuring of LEA. However, this occurred not because of the validity of the arguments presented, which were limited and poorly articulated, but rather in spite of them. In fact, if I were to evaluate the quality of these critiques on academic grounds, they would merit an F. The logic was fragmented, the language rife with rhetorical fallacies, and the underlying assumptions revealed a narrow worldview incapable of engaging with the complexity of the issues at hand. Yet the impact arose because the criticisms encountered a mind willing to explore the issues raised, regardless of the quality of the critique.

This willingness to engage with even the most flawed critiques stems from a commitment to intellectual openness, a belief that truth can emerge from the most unlikely sources if one is attentive to the underlying tensions and unarticulated questions. In this sense, my response to these emails was not a defensive rejection of their content but an opportunity to reflect on the broader societal conditions that produced them. The anger, frustration, and disillusionment expressed in these emails, while often misdirected, are symptomatic of a deeper malaise—a disillusionment with the structures of power that govern academia, labor, and intellectual life.

Beyond the Immediate Critique

If I were in that student’s position, I might have written something satirical, aiming to criticize while attempting to engage constructively. Criticism, when leveled without any attempt at understanding or empathy, serves little purpose beyond alienating those it targets. However, a well-crafted critique—one that recognizes the complexity of the issues at hand—can foster dialogue, challenge assumptions, and lead to meaningful change. The critiques I received, while lacking in nuance, forced me to confront uncomfortable truths about the systems in which I participate, and they pushed me to reconsider how best to navigate the complexities of unpaid labor, academic expectations, and the future of LEA.

The changes I am now implementing at LEA are a direct response to these reflections. We are shifting toward a more transparent model in which contributors are compensated whenever possible, and where voluntary participation is structured with clear guidelines to avoid any appearance of exploitation. This restructuring is not a panacea, nor does it fully resolve the tensions between labor and compensation that have long plagued academic publishing. However, it is a step toward creating a more equitable system, one that recognizes both the material realities of academic labor and the intellectual generosity required to sustain the humanities.

Toward Radical Change

The broader question remains: How do we generate true alternatives to the current system? In many ways, this is the most challenging question we face. The systems of power that govern academia, publishing, and labor are deeply entrenched, and their fascistic tendencies are often masked by the rhetoric of professionalism, meritocracy, and excellence. Yet, as I reflect on my own participation in these systems, I am increasingly convinced that radical change is both necessary and possible.

To generate true alternatives, we must begin by acknowledging our own complicity in these systems. As scholars, editors, and educators, we are often caught between the ideals we espouse and the practical realities of our professional lives. The challenge is to find ways to align our practices with our values, to create spaces where intellectual labor is valued not only for its output but for the process through which it is produced. This means rethinking the very structures of academic publishing, tenure, and labor relations. It means pushing back against the corporatization of the university and the increasing reliance on unpaid or underpaid labor to sustain intellectual production. And it means fostering a culture of engagement, where difference is not merely tolerated but embraced as a vital component of intellectual life.

The two emails served as a catalyst for this reflection, not because they were particularly insightful, but because they forced me to confront the contradictions inherent in my own work. The frustration expressed in these emails mirrors my own frustration with a system that often values compliance over creativity, efficiency over thoughtfulness, and profit over intellectual growth. The challenge, then, is to find ways to resist these tendencies without retreating into cynicism or disengagement. We must find ways to create meaningful alternatives, even if they are imperfect, provisional, and contingent.

The Satire of a Neo-Serf: A Hypothetical Critique of Unpaid Internships

Had I been in the shoes of that student criticizing my proposed unpaid internship, the following satirical email would have captured my critique while opening a space for dialogue:

Subject: A Proposal for a Neo-Serf’s Apprenticeship

Dear Professor Aceti,

I am so delighted to welcome you to our school, and I eagerly anticipate the wonderful opportunities you will bring to exploit—pardon, mentor—students such as myself.

Thus far, I have not yet experienced the advanced forms of capitalistic exploitation that are customary in the United States. However, I sincerely hope that my European training in miserization and pauperization will sufficiently qualify me for the chance to work with—or perhaps even be exploited by—you. Given your critical writings on neo-serfs, I take great pride in having already become one myself and am eager to deepen my understanding of this post-postcapitalist condition under your esteemed guidance.

I have heard that you neither eat nor sleep and are capable of working without pause, a feat of legendary endurance. I aspire to learn these and other valuable skills from you, to help me succeed in acquiring unpaid internships and cultivating my career as a professional neo-serf.

Please do not mistake my tone for hostility or bitterness. I am currently working hard to eliminate sarcasm from my professional communications and remain hopeful that under your tutelage, I will learn to engage in pleasantries devoid of rancor. Perhaps we could further this conversation over a drink. In fact, as a testament to my dedication to a career in the arts, I will work an extra shift this weekend to ensure that I can host you and show you a good time in our city, so that we may discuss the finer points of exploitation with mutual candor.

Yours sincerely,

Lanfranco Aceti

Sarcastic Criticism and Openness to Dialogue

This hypothetical email, while sarcastic and laced with critique, would have offered an opportunity for dialogue and reflection on the deeper implications of unpaid labor in the arts. It is a critique I would have welcomed—not because it flatters, but because it engages meaningfully with the question of exploitation in the context of higher education and artistic mentorship.

Sarcasm, when wielded skillfully, can be a powerful tool for exposing the absurdities of entrenched systems. In this case, the student’s hypothetical critique highlights the contradictions of the modern academic-industrial complex, where unpaid labor is often justified under the guise of “opportunity” and “professional growth.” This email, though biting in tone, does not merely dismiss my proposal; instead, it invites further conversation and opens the door for a more nuanced understanding of the tensions that exist between mentorship, financial compensation, and the value of intellectual exchange.

Reflections on Mentorship and Unpaid Labor

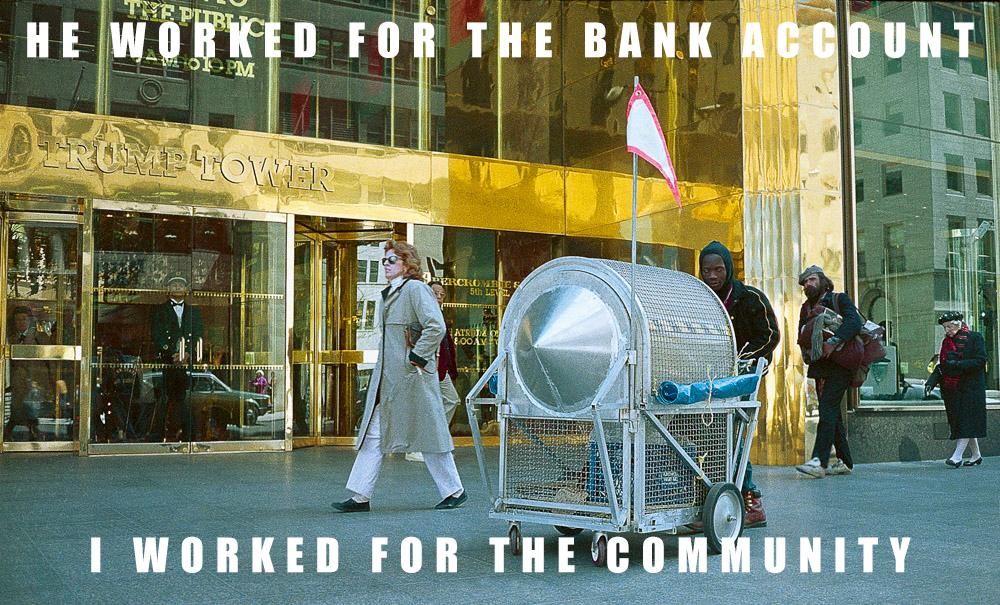

I owe this perspective to Professor Krzysztof Wodiczko, a mentor whom I profoundly admire for his candor, frankness, and ability to engage in heated debate without harboring resentment. Years ago, Professor Wodiczko allowed me to work as an unpaid artist/researcher at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) while I was completing my Ph.D. at Central Saint Martins. During that time, he offered his knowledge freely, helping to advance my understanding of art and fine art research, without the expectation of financial compensation.

This arrangement, though unpaid, was an invaluable experience—one that contributed significantly to my intellectual and artistic growth. The exchange of ideas and mentorship I received from Professor Wodiczko exemplified what unpaid labor can achieve in certain contexts: the possibility of true intellectual exchange, not constrained by monetary transactions but rather grounded in mutual respect and the desire for growth.

However, it is important to note that my experience with unpaid labor was shaped by a very specific set of circumstances: the generosity of a mentor who, despite the absence of financial compensation, offered his time and expertise without exploiting my labor. Such an arrangement, in the current academic landscape, is exceedingly rare, as the structures that govern academia increasingly reflect the logic of neoliberalism and corporate exploitation. Today, the demand for unpaid or underpaid labor often comes with little in the way of mentorship or intellectual exchange, reducing students to mere cogs in a bureaucratic machine that prioritizes profit over growth.

Moving Forward: Rethinking Unpaid Labor in the Arts

This hypothetical critique of my proposal for an unpaid internship forces me to confront the difficult question of how we, as educators and mentors, can foster meaningful intellectual growth without perpetuating the exploitative systems that dominate higher education. How do we provide opportunities for students to engage with the arts, to learn and grow, without asking them to sacrifice their financial well-being in the process?

One possible solution is to rethink the structure of unpaid internships altogether, creating opportunities that are transparent, structured, and mutually beneficial. If financial compensation is not feasible, then we must ensure that students are receiving meaningful intellectual mentorship and that their labor is recognized, not as a means to an end but as a valuable contribution to the academic and artistic community.

In conclusion, the hypothetical email, though sarcastic, is a valuable critique that I would have welcomed. It reflects the very issues I seek to address in my work: the tension between labor, compensation, and intellectual exchange, and the ways in which we can create more equitable systems within academia and the arts. Professor Wodiczko’s example serves as a reminder that unpaid labor can be valuable when conducted in the right context—when it is grounded in mutual respect and a shared commitment to intellectual growth. However, we must remain vigilant in ensuring that such opportunities do not devolve into exploitation, and that we, as mentors, are providing students with the tools they need to succeed in their chosen fields, both intellectually and financially.

Image 3. Lanfranco Aceti, Whose Work?, 2024. Meme with documentation of a work of art by Krzysztof Wodiczko. Dimensions: variable. Krzysztof Wodiczko, Homeless Vehicle, 1988-1989. 5th Avenue, New York, 1988. Photograph courtesy of Museum of Art in Łódź.

While I gleaned a few valuable lessons from the two rather poorly crafted emails and memes, I must admit to a certain level of disappointment. I expect, and indeed demand, a degree of wit from artists—particularly those engaged in the digital age’s meme culture, where the sharpness of thought should be reflected in the medium itself. Memes, after all, are a form of visual rhetoric, and with that comes the responsibility to wield them with intelligence and creativity. The emails lacked this depth. I find it disheartening that the opportunity to engage in more meaningful, satirical commentary was missed, especially in a medium that can be so potent.

That said, I hope I was able to impart at least two crucial lessons in return—though my naturally pessimistic outlook leaves me uncertain as to whether they were received.

The first lesson is that an argument can—and indeed must—be articulated with intelligence. It is not enough to rest on the banalities of overused stereotypes or the intellectual laziness of clichés. As artists and thinkers, we have a responsibility to elevate discourse, to challenge conventional thinking, and to communicate complex ideas in ways that are not merely accessible but thought-provoking and nuanced. Resorting to the lowest common denominator in terms of rhetoric diminishes not only the argument itself but also the potential for genuine dialogue and understanding. If the argument lacks sophistication and insight, it not only fails to convince but also betrays the intellectual rigor that is expected of anyone wishing to participate in critical debate. The role of the artist, as well as the scholar, is not to indulge in oversimplification but to confront complexity head-on, using language, imagery, and argumentation to create spaces for real engagement.

Image 4. Lanfranco Aceti, I Am Coming for Your Ass, 2013. Print on poster paper. Curator: Artemis Potamianou in the photo, in Athens.

The second lesson is one that is perhaps less intuitive: that silence, while often misinterpreted as acquiescence, is not synonymous with surrender. In fact, my prolonged silence on the matter—almost a year, to be precise—should not have been seen as indicative of passivity or concession. Rather, it was a period of deliberate reflection, a space in which I could critically assess not only the content of the criticisms directed towards me but also the broader frameworks and systems in which these critiques were embedded. Silence, in this sense, can function as a deliberate intellectual strategy. It provides the necessary distance to evaluate complex situations with the clarity and depth they deserve, as opposed to responding immediately, impulsively, or defensively. Silence, far from being passive, is often an active engagement, offering a form of resistance against the pressure to respond prematurely and shallowly.

To presume that a lack of immediate response equates to ignorance or defeat is to fundamentally misunderstand the dynamics of thoughtful discourse. In both scholarly and artistic pursuits, time and contemplation are often necessary to generate responses that rise above the superficial and the reactive. An immediate reply may satisfy the demand for quick engagement, but it rarely offers the level of insight that deeper reflection can yield. Therefore, silence should not be mistaken for capitulation but understood as an opportunity for intellectual processing, allowing for a response that carries greater precision and depth of insight.

In closing, I want to underscore that these moments of criticism—though poorly articulated—were not without value. They offered me an opportunity to reflect on the broader issues at hand, including the state of discourse, the role of artists and thinkers, and the modes of engagement that we choose to adopt. However, for those who aim to critique, I would offer this advice: elevate your rhetoric. The world does not need more reductive arguments or superficial memes; it needs more nuanced, intelligent, and challenging conversations.

The Economics of Intellectual Labor

The previous analysis sought to illuminate the structural mechanisms of contemporary publishing in the humanities, particularly through the lens of financial sustainability. Is it even possible to quantify the value of what has been produced by LEA or similar humanities publications? While it may seem tempting to evaluate such ventures through a purely monetary scale, such metrics prove inadequate and reductive. The intellectual labor involved in developing, curating, and sustaining these publications escapes quantification, as do the invisible costs associated with securing partnerships, fostering collaborations, and maintaining growth over time.

These intangible contributions—comprising both intellectual and financial commitments—are often borne by institutions that recognize the cultural importance of open-access journals, especially those operating independently of the corporate structures that dominate the contemporary art world. Such institutions are becoming increasingly rare, surviving within ecosystems that either offer financial security or uphold societal values that challenge the transactional models of modern academia.

It is within this precarious ecosystem that I must acknowledge the significant contributions of three individuals without whom LEA’s survival might have been compromised: Professor Mehmet Baç, the former Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) at Sabanci University; Haluk Bal, the General Secretary at Sabanci University; and the current Dean of FASS, Müftüler-Baç. Their support was not just rhetorical but practical, providing critical resources and intellectual backing that enabled LEA to flourish during my time at Sabanci University. It was their belief in LEA’s international significance that fortified its position amidst an increasingly competitive and financially constrained academic environment.

Unfortunately, such institutional backing is an anomaly in today’s academic landscape, as universities continue to reallocate their resources towards profit-driven models, leaving projects like LEA to survive in the interstitial spaces between institutional support and individual sacrifice. This precarious existence is sustained by the labor of volunteers who dedicate their time and expertise without compensation—labor that is critical for these platforms to endure and for meaningful discourse to find a home.

The absence of sustained institutional support presents even harsher conditions for survival. Universities, despite offering no direct financial contributions, continue to leverage such outputs to bolster their own scholarly reputations, engaging in what can only be described as a form of intellectual exploitation. The disconnect between labor and reward becomes all the more evident when considering how these institutions appropriate the fruits of such endeavors, while failing to address the burdens of their creation.

A modern manifestation of this exploitation is found in digital platforms, which, under the guise of increasing accessibility and visibility, shift the burden of metadata creation and formatting standards onto editors and scholars. These additional tasks, rarely acknowledged, represent a new frontier of academic labor exploitation, a direct import from the corporate model of digital delegation. Rather than lightening the workload, these platforms impose further demands on the already overextended contributors, while the financial burden continues to be absorbed by those producing the scholarly content, not the institutions that profit from its prestige.

To illustrate this point, I include an excerpt from an email exchange—names omitted—that vividly highlights this shifting of labor responsibilities.

Hi X,

I don’t recall discussing this particular point. What I do remember is that we talked about having a dedicated person to handle the uploads for both the backlog of LEA’s publications as well as the forthcoming issues. This was something that was made clear.

Given this shift in responsibility, I’m hesitant to commit. This approach effectively shifts additional labor away from Z University and onto me. The larger question here is: why should I take on this additional work? It doesn’t seem like there is a mutually beneficial structure in place. I would be happy to have the work done, but only if it’s compensated appropriately.

These platforms have increasingly become sites of labor exploitation, shifting work hours and financial responsibilities from institutions to individuals. I’m wary of contributing to or facilitating these post-capitalist dynamics in corporate education.

To give a definitive answer, I would need to assess the platform to determine the workload involved. If the task amounts to 30 minutes to an hour per issue, involving around 20 essays, it may not be excessively burdensome. Anything more than that should, in my view, be compensated.

All the best, as always,

Lanfranco

The rise of these digital platforms mirrors a broader shift in the post-capitalist economy, where the burdens of unpaid labor are systematically transferred from institutions to individuals. What is often framed as “academic service” or a benign necessity for maintaining scholarly networks is, in truth, a cost-saving mechanism designed to extract intellectual labor without proper remuneration. This dynamic entrenches a form of labor exploitation that is increasingly pervasive in academic and cultural sectors, where institutions capitalize on the unpaid work of scholars, editors, and contributors under the guise of altruism or professional duty.

However, acknowledgment and reciprocity are critical in navigating such exploitative frameworks. It is not enough to merely participate in these systems; one must seek out and foster relationships with the individuals and institutions that genuinely support intellectual and cultural work, particularly those that enable the creation of “interstitial spaces”—environments that, while precarious, allow for critical expression and scholarly growth outside corporate or institutionalized boundaries. These fragile spaces offer an essential alternative to the market-driven dynamics that now dominate academia and the art world. By supporting these spaces, we can resist the commodification of intellectual labor and foster environments where creativity, intellectual rigor, and meaningful discourse can thrive despite the systemic pressures to conform to corporate models of efficiency and profitability.

Consequences: Intended and Unintended

The proposed editorial model aims to introduce three key outcomes, each designed to enhance the efficiency, equity, and intellectual rigor of the editorial process.

First, this model is intended to streamline the publication process by ensuring that submitted manuscripts adhere to the journal’s in-house style from the outset, thereby reducing the need for extensive grammatical and stylistic revisions. By refocusing editorial efforts from basic copyediting toward more substantive engagement with the structure, methodology, and argumentation of the submissions, editors can provide meaningful feedback that enhances the scholarly impact of each article. Mandatory adherence to the Chicago Manual of Style for citations and bibliography will establish a higher baseline for submissions, and authors will be incentivized to submit thoroughly polished work. Articles requiring significant editorial intervention—whether for language or formatting—will incur higher submission costs. This fee structure not only discourages subpar submissions but also accelerates the review process, allowing high-quality work to be published without undue delay. Consequently, the value of the editorial labor becomes more visible, and the published articles reflect the rigor and investment made by both authors and editors, ultimately raising the overall standard of LEA’s publications.

Second, this model directly addresses one of the most persistent issues in contemporary academic publishing: the exploitation of editorial and peer-review labor. By instituting a system of financial compensation for editors and reviewers, LEA can both attract skilled professionals and ensure that their labor is properly acknowledged. Compensation incentivizes faster, more thorough reviews, and also positions LEA as a more attractive and ethical option for both contributors and editorial staff. Moreover, eliminating the reliance on unpaid labor creates a more sustainable and just publishing ecosystem, one that values the intellectual work of its contributors. In this model, transparency is paramount: the names of peer reviewers will be publicly listed for each article (except for those participating in blind review), offering explicit recognition for their contributions. By making these intellectual efforts visible, LEA moves toward a more equitable model of academic publishing, challenging the culture of invisibility and exploitation that currently dominates the field.

Third, this model aims to eliminate the pervasive sense of exploitation that often characterizes both contractual and volunteer editorial frameworks. By clearly delineating the boundaries between paid and voluntary labor, LEA offers contributors two distinct modes of participation: a transactional model, in which editors and reviewers are compensated for their expertise, and a volunteer-based model, in which individuals contribute their labor out of a shared commitment to the project’s intellectual and cultural goals. In the latter case, the onus is on LEA to cultivate a sense of intellectual community and to generate sufficient interest in its content, thus attracting volunteer editors and reviewers who are motivated by a genuine belief in the journal’s mission. This distinction fosters a more transparent and equitable relationship between contributors and the journal, rooted in mutual respect rather than the exploitation of unpaid labor. As a result, LEA positions itself as an exemplar of ethical editorial practice in an increasingly corporatized academic landscape.

Unintended Consequences: Navigating Equity and the Burden of Persuasion

An anticipated but unintended consequence of this new approach is that authors lacking the financial resources for the contractual route will be compelled to convince LEA editors of the intellectual merit and potential impact of their projects. This requirement places a heavier burden on emerging scholars, particularly students and early-career academics who may not yet have the professional networks or reputations to support such negotiations. However, in advocating for an equitable system—driven by those concerned with fairness—there emerges an obligation to ensure that all parties are equally considered in this framework. Thus, the responsibility for persuading editors now rests with these authors, who must articulate the value of their contributions to LEA’s editorial team. In doing so, they confront a question often posed to mentors or collaborators: “What’s in it for me?”

Does this new model solve all of the problems inherent in academic publishing? Certainly not. Several issues remain unresolved, including my own longstanding volunteer relationship with Leonardo/MIT Press, a commitment I have sustained for years without public complaint, despite the exploitative nature of unpaid labor in service of the journal’s mission. This labor, dedicated to advancing Leonardo’s international reach and preserving cultural documentation, has not been formally recognized or financially compensated, a reality that I have accepted in silence until now.

The grievances that prompted this essay, however, reveal a crucial insight: raising one’s voice can sometimes effect meaningful change. The assumption that customary practices—entrenched through years of professional norms—will persist without scrutiny or challenge has been decisively debunked. Indeed, questioning these practices can force institutions to reconsider and realign their approaches, even in the most tradition-bound sectors of academic publishing.

As an experimental journal, LEA has a responsibility—at least from the perspective of this author—to continue exploring alternative practices and models for intellectual collaboration. Its mission should be dynamic, responsive to the evolving landscape of contemporary art and academia. Yet this experimentality also compels us to revisit and challenge established norms, especially those that have long exploited scholars and practitioners without offering substantive reciprocal benefits.

Moreover, these recent developments bring into sharp relief the fragile nature of the relationship between academic volunteers and publishers. This relationship exists outside of formal legal frameworks, often devoid of contracts or binding agreements, leaving it precariously vulnerable to abrupt termination. A publisher can sever this bond at any time, without recourse or protection for the volunteer. The entire dynamic rests on a foundation of trust and mutual commitment, but it remains perpetually susceptible to rupture. For scholars and editors alike, this fragility underscores the need to reimagine more sustainable, ethical, and legally protected structures of academic labor.

As Brian Nosek incisively observes, “”Academic publishing is the perfect business model to make a lot of money. You have the producer and consumer as the same person: the researcher. And the researcher has no idea how much anything costs.’ Nosek finds this whole system is designed to maximize the amount of profit. ‘I, as the researcher, produce the scholarship and I want it to have the biggest impact possible and so what I care about is the prestige of the journal and how many people read it. Once it is finally accepted, since it is so hard to get acceptances, I am so delighted that I will sign anything — send me a form and I will sign it. I have no idea I have signed over my copyright or what implications that has — nor do I care, because it has no impact on me. The reward is the publication.'” [9]

This statement reveals the fundamental exploitation inherent in both academia and academic publishing, exposing a system designed not for the enrichment of intellectual communities but for the consolidation of corporate profit.

The precariousness and corporate exploitation endemic to these sectors are not incidental but systematically structured at the highest levels, driven by pressing needs and branding imperatives. At the heart of this system lies a tension between the real or perceived necessity of publication and the reputational economies that dictate academic advancement. To ascend professionally or to fulfill some larger social or ethical mission, one is led to believe that holding a prestigious editorial position or producing a prolific publication record is a non-negotiable requirement. This entrenched belief reinforces exploitative practices, creating a cycle in which both academia and the corporate nonprofit publishing world thrive on the uncompensated labor of scholars.

The argument that “I have personally benefited from my volunteer activities, and therefore my time has been repaid” collapses under scrutiny. First, it is based on a flawed assumption: my years of unpaid editorial work have not yielded substantial professional rewards. Far from securing employment or enhancing my career trajectory, these activities have, at best, served as marginal contributions to my academic profile. Second, this logic is frequently extended to authors, who are often told that the mere act of publication is adequate compensation for their labor. This reasoning leads to a dangerous conclusion: that scholars should work for free in perpetuity, for the benefit of corporate publishers and academic institutions that claim to offer prestige in lieu of remuneration.

In reality, the purported “benefits” of this system are often illusory. The promise of future professional advancement or intellectual acclaim does not translate into concrete economic gains or increased social mobility. The rewards are largely symbolic, fulfilling an abstract sense of duty or contributing to an individual’s intellectual journey. However, they rarely lead to material rewards—no lucrative contracts, no pension funds, no luxurious holidays in far-flung locales.

The primary beneficiaries of this system are, predictably, the publishing and academic industries themselves. These entities receive vast amounts of unpaid labor that would otherwise demand compensation. Editors, peer reviewers, and contributors are continuously asked to donate their expertise and intellectual labor, bolstering the institutional prestige of journals and academic publishers while receiving only nominal acknowledgment in return. The very structures that enable these industries to function are built on the unpaid labor of scholars, whose time and intellectual capital are harvested to maintain the operational success of the system.

This state of affairs not only undermines the value of scholarly labor but also perpetuates a system that privileges institutional gain over intellectual and ethical reciprocity. The task before us, then, is not only to critique these practices but to actively rethink and rebuild the systems that underpin academic publishing. It is imperative that we challenge the entrenched norms that devalue scholarly contributions and explore alternative models that prioritize fair compensation, transparency, and ethical engagement in the production and dissemination of knowledge.

To Conclude: Give Me My Porsche!

To begin rethinking the operational models of these institutions, we might consider adopting straightforward measures: ceasing to review scholarly work without compensation, for instance. This would mark a simple but profound shift in how we assess the value of our labor. We should also pose a fundamental question—one that my students ask, either directly or indirectly: “What’s in it for me?”

This is not merely rhetorical. It’s a critical tool for assessing the fairness of our professional contributions. By addressing this question, we challenge the prevailing norms of unpaid labor in academic publishing, and push for systems that recognize and reward the intellectual and editorial work that sustains it. In doing so, we foster a more equitable framework that values the contributions of all participants in the scholarly ecosystem.

Societal conflicts today often pit advanced capitalism against a post-postmodern perspective that resists exploitative operational frameworks. Participants in this digital age—like modern-day neoserfs—are fractured and divisive, critiquing these systems but often failing to challenge or reconstruct the social structures that would give visibility to marginalized research and unconventional thought. This underscores the urgent need for deeper, more nuanced questions—ones that cut through superficial platitudes and tropes.

Image 5. Lanfranco Aceti, Me!.. Me!… Bitch All that You Can Bitch, 2018. Meme. Inspired by Tyra Banks.

At this point, I cannot resist humorously invoking Tyra Banks: “Be all you can be, not bitch all you can bitch.” While amusing, the statement reflects a deeper issue—the need to engage in intellectually rigorous argumentation rather than recycling hollow critiques. We must go beyond pixelated expressions of discontent and strive for real change.

More critically, dialogue should not be a tool for shutting down others, but rather a mechanism for intellectual exchange, even when challenging. Dismissing others or resorting to self-righteousness within echo chambers only deepens the division in contemporary societies, contributing to what I can only describe as fascistic tendencies within digital communities. Instead, true dialogue can help foster renewed understanding of ourselves, our projects, and our interlocutors. The nature of these exchanges parallels the fragmentation of society itself.

The last part of the twentieth century saw foundational concepts like society, citizenship, and solidarity eroded, and we are still grappling with the consequences. Academia and the nonprofit publishing sector have fallen into a consumeristic model, exploiting knowledge for career advancement rather than fostering intellectual development. This dynamic is worsened by digital frameworks that offload labor onto many while concentrating revenues among the few—a parasitic system reminiscent of Kafka’s The Castle. We are trapped, dutifully performing bureaucratic tasks with delusions of improvement, all the while obscuring the true nature of contemporary humanity and the role of knowledge within it.

Knowledge, now a twenty-first-century commodity, has been degraded, reduced to a mere transaction rather than a valued asset. Both the sellers and buyers of this commodified knowledge are complicit, bringing to mind the Oscar Wilde adage: “They know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” [11]

In response to these dynamics, I have shifted focus from the price of publishing to its value. By instituting a pricing structure for LEA’s efforts—a move that may seem paradoxical—I aim to highlight and reinforce the intrinsic value of the publication, the labor behind it, and the commitment of those who contribute their time and expertise. This initiative seeks not only to challenge prevailing paradigms but to cultivate a deeper appreciation for the intellectual and ethical contributions that sustain scholarly work.

As I revisit this essay in 2024, I am acutely aware of the significant changes that have taken place since its inception in 2018. The years between, marked by a global pandemic, two wars, and numerous international crises, have profoundly altered my perspective on scholarly engagement and publishing. These developments have made it abundantly clear that I can no longer sustain my volunteering involvement with LEA, Leonardo/ISAST, and MIT Press. My decision to sever these ties after 15 years arises from a longstanding commitment to end my participation in unpaid labor and forms of financial abuse, despite my natural inclination to offer advice and volunteer contributions. The threshold of exploitation has been crossed, and it is undeniable that my intellectual labor deserves fair compensation.

My frustration with cultivating a publishing environment that disproportionately benefits others has led me to reassess my scholarly approach. While I continue to produce essays and chapters for editorial houses as part of my scholarly obligations—though these contributions remain unpaid—I have become increasingly attuned to the imbalances inherent in the publishing process. This awareness encompasses both the exploitation on the side of publishers and the burdens placed on those submitting work. Recognizing these complexities has spurred me to redirect my efforts toward self-sustaining platforms. Today, I possess the tools, capabilities, and motivation to publish my work independently on my website. This shift grants me the freedom to craft more comprehensive and nuanced essays, free from the constraints imposed by traditional publishing, and allows me to prioritize ideas that I believe are truly worth documenting and sharing.

This transition represents a deeper commitment to meaningful intellectual engagement, untethered from the pursuit of arbitrary academic metrics that often fail to measure true impact or significance. It also avoids the engagement with toxic digital communities that increasingly have come to represent the worst instincts of mankind. The analyses in this essay serve not only as a reflection of my past experiences but also as a roadmap for my future endeavors. I am in the process of developing a new, innovative platform—Observations, Creations, and Reflections (OCR)—a digital space that will function as both a repository of writings and a site for critical discourse and social development. OCR will focus on the regeneration of communities devastated by the post-modern scourges of abandonment, resource scarcity, and a dearth of administrative and managerial acumen. This project stems from a desire to create a space for art and literature to foster renewal and resilience in these marginalized spaces. (For reference, see OCRadst.org).