“Life is a serendipitous set of circumstances. Talent, hard work, and connections count for naught. Not in the long run. The ability to prostitute oneself across multiple media platforms does.”

Dolores de Alma Blanca

ABSTRACT

This essay explores the complex dynamics between relational and prostitutional aesthetics in contemporary new media art, emphasizing the critical necessity for a profound reevaluation of media’s role in society. The term “prostitutional aesthetics” refers to the commodification of art and the artist’s role, where self-representation and media engagement are driven by a relentless pursuit of visibility and validation, often at the cost of substantive meaning and social critique.

Lanfranco Aceti incorporates personal anecdotes and theoretical reflections to underscore the superficiality of technologically mediated art. The essay argues that the current celebration of prostitutional aesthetics perpetuates existing patriarchal and capitalist structures, transforming art into a vehicle for self-promotion rather than a means for genuine social critique and engagement. This commodification is evident in the way artists and their works are often co-opted by market forces, prioritizing visibility and marketability over artistic integrity and critical depth. Through this lens, the author explores relational assonance in art, inspired by matriarchal values. It envisions a future where art transcends its digital confines to foster genuine human connections and a symbiotic relationship with the world.

KEYWORDS: Prostitutional Aesthetics, New Media, New Media Whores, Censorship, Art Practice, Contemporary Art

Introduction: Relational Aesthetics onto a World of Undying Dead

When thinking of relational aesthetics one of the first thoughts is about the self in relation to the world. This is a world of astonishing new media (new for but a few seconds), mindless entertainment (before quickly jumping on the next fad), and technological wonders (until they come crashing down, weighted by their own social and environmental costs). More than anything else it is a world characterized by human stupidity and its attempt to establish relational aesthetics. Grandiose stupidity, rarely, and most often sheer stupidity in the quest for short-term illusory gains. There is one important element in this introduction to understand, and that is the meaning of Prostitutional Aesthetics—the title of a book I am writing—and why prostitutional aesthetics are pertinent to an aesthetic of relations.

The mode of perceiving the world is through a selfish lens, particularly the lens of people who are identified in this chapter as New Media Whores. They are selfishly absorbed in the construction of their selves and their success even if it means using ethical values as weapons of both defense and offense. These are people who exchange the value of transformation achieved through a personal journey which obliges one to traverse, engage, and understand the world—methodologically transitioning from a personal perspective to a universal one—for a blunt system of affirmation of the self, conceived and presented as immutably perfected through a process of permanent self-promotion as a constant reaffirmation of the self. For them, it is as if the marketing of the ego somehow makes the rest of the world aware of their perfection and not of their stupidity in being new media whores.

The Urban Dictionary divides Media Whores into three distinct subcategories.

“1. The ‘loner’ – this whore will go on to a social media and suck the life out of one single target looking for friendship. 2. The ‘twit’ – these whores are twitter ‘over-users’, who post crap about their lives that nobody needs to know. 3. The ‘leech’ – these whores absorb the creative works of others, then shit it out as a big bunch of uselessness, which they spam all over the internet.”[1]

The chapter is an analysis of this world and these people through the lens of aesthetics and new media theories, not a panacea and perfect solution to existential woes. It is an analysis of an imperfect and collapsing phase in a larger historical trend, which might have, at some point, the extinction of humanity as its final result.

To the critics of my approach, typically optimistically blind and imperialistic Anglo-Saxons with their cohorts of emulators and supporters, I would like to remind that the birth of a species implies necessarily the possible outcome of its collapse at some point in time. Only what is not born does not die.

Or, more nuancedly phrased, only what is unborn might not have the possibility of dying.

New media sell a new idea of immortality by offering the illusion of not dying and by detaching the enslaved consumer from the understanding of and the engagement with the state of nature. New media facilitate, as the ultimate form of subjugation, an eternally permanent condition of exploitation within which much of humanity, reduced to basic trash in the form of undying dead, can be pigeonholed.

It is a digital Procrustean bed in which the digital pixel acts as the constraining box in which all have to fit and in which the relations are pre-foreseen and pre-established by an algorithm rooted in a Cartesian grid that eliminates the state of nature by neatly placing it in a pre-formatted container.

The aesthetic relations in this chapter are linked to an experience which, although removed from the digital as sole modus of production, goes back to the state of nature in an attempt to salvage personal relations and personal development. It proposes an idea of the ‘universal’ that is inclusive and not exploitative, colored but not segregated, different but not discriminatory. For this reason, the chapter is constructed in a rather unusual manner with events that appear to be unrelated, but that nevertheless have a strong relation to the experience, understanding, and refusal of a thanatophobic world filled with undying dead and devoid of humanity.

In this world of media whores in general, and new media whores in particular, vacuousness is celebrated and hollowed-out relations—based on a constant prostitution of the self to accumulate capitalistic gain—generate and display the ontology and phenomenology of prostitutional aesthetics.

Prostitutional aesthetics can be defined as the participation in and total acceptance of new media whores’ capitalistic accumulation of meaningless values for a continuously celebrated and celebratory affirmation of the self in a virtualized life that no longer appears to be linked to the real.

Once Slaves, Now Trash and Whores

The remit of this essay is to offer examples of new media works of art that failed and by failing showed the marginalization of new media art at a time in which it was neither fashionable nor aesthetically welcome. My practice moved in between the two worlds, that of the virtual and of the real, not so much in an attempt to bridge them but more to show the idiosyncrasies of processes, behaviors, and realities.

I never considered the virtual as something ‘other’, but as something real that existed and had real consequences in real life despite its ‘virtual’ status. I even argued that an illusion was real since it was part of the physical world and with real consequences in the world and for those who experienced the illusion. To put it more clearly, if you die in the Matrix you die in the real world and vice versa and the illusion affects you and everyone around you, real or virtual as they might be. Unless one separates the body from the soul, the brain, or both. Although, even in this case the storage in which the essence of a human being is allocated to permanently live in an illusory state might be destroyed or consumed by external events. If there is a physics and chemistry to biology, the same physical and chemical rules apply to transistors and chips. Death comes for all, real as well as virtual beings.

It was in 2003 that I realized the online version of a project, which began in Detroit in 1999, titled SLAVES4SALE.COM. It was further developed while at the Center of Advanced Visual Studies at MIT with Professor Krzysztof Wodiczko and with the support of Professor William Uricchio at the Department of Comparative Media Studies at MIT. The whole project is now an empty domain space being sold for: $2,495.

I am talking about this particular new media art project because it was a failure on multiple planes (both real and virtual). One of my Mac laptops crashed and I lost most images, despite paying 600 pounds to have them retrieved. Not much remains on the Internet about it since with time the Internet tends to forget—or, better phrased, the past memories die out if not financially supported—and not many traces are left of exhibitions, aside from a few images that are dispersed on my hard drives. Things online and digital, after some time, evaporate, reminding us all that immortality in the virtual is perhaps only afforded to those who have the financial resources to archive and constantly update.

Image 1: Lanfranco Aceti, The Box Returns, 2022. Cardboard box (realized in 1998 and returned from MoMA in 1999; dimensions: 23 cm. x 28.8 cm. x 13.5 cm.) and undeclared contents. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm.

Once Slaves, Now Trash and Whores

I liked, and still love, the failing-to-exist of this project. It is a successful failure in archiving, mixed with the other many failures starting from its first public exhibition in Leeds as a wall of cardboard boxes. Each box had one side covered with paint, drawings, or collages.

The initial box made in Detroit sparked the idea for a subsequent project I called The First Box. This project consisted of creating four small boxes and sending them to: MoMA’s Director Glenn D. Lowry, one to Queen Elizabeth II (I was living in the UK at the time), one to then Prime Minister Tony Blair, and one to Nicholas Serota, Director at Tate Modern.

Only the box from MoMA was returned with a letter explaining that the museum would not accept donations of contemporary art. The letter has been lost in one of my many moves. The other boxes, it is my guess, were destroyed. It is from the very beginning that this project was plagued by issues of disappearance, nevertheless it endured by finding spaces and visibility in shows and publications. My explanation to the tribulations of the project and its many manifold manifestations through the years was that a used cardboard box was too much arte povera, which definitely could only be perceived as anything and everything else but art.

The works of art, even as an online manifestation on e-Bay, caused concern and they were almost censored. The first online exhibition took place in Bangkok in 2004 at the New Media Art Festival where, with Inspector-London at ICECA 2004, I presented Slave BOX#20 from SLAVES4SALE.COM. This is the show where one of the boxes appeared on eBay for the first time and where I would be for sale as a slave.

At the time I was studying and working on the processes of commodification of the digital and it seemed to me to already be carrying nefarious consequences. I decided to showcase what I saw as the beginning of a path of exploitation by a) selling myself as a slave and b) continuing to explore the extent of contemporary commodification, labor practices, and financial enslavement.

Eighteen years later and after several days of excavation in my personal archive—a process of media archeology if you wish, since I had to resuscitate pieces of software that had since that time disappeared—I was able to find some material. It was exciting to remember that the first proto-artwork of the very first box was realized in Detroit and filmed there in black and white. It was also in Detroit that this proto-artwork was ‘exhibited’ for the first time in an off-off-off event where we were all gathered around a barbecue.

The proto-artwork—approximately 50 cm. x 20 cm. of which I can’t remember the title or the location, since I believe it might be in some attic somewhere in Detroit if it has not been destroyed—became a larger installation of 250 cm. x 300 cm. made of twenty boxes, each one numbered and named. I felt that the boxes were individuals and so I gave them names.

Slaves4Sale.com‘s boxes were exhibited again on eBay with Inspector-London for Bangkok and London-based shows, but also physically displayed in a show in the East End of London and for an exhibition in Leeds. While the international shows and the ones in London had fewer problems with the works of art and their format, the presentation in Leeds during a formal gallery show was short of a disaster. I had driven a van from London to Leeds, without having previously ever driven a car on the left side of the road, to transport to an exhibition twenty empty boxes that could not be folded. The space allocated was in a quiet corner of the gallery space. The curator was laughing happily with her assistant about me and the works of art — she had seen photos of them and had measurements, but I guess she expected something sleeker and more corporate—and only scowled when she realized that the rest of what she had chosen did not fit in with my wall of boxes. My works of art clamored for attention and did not glamorously or harmoniously blend with the others. I got the cold shoulder for the evening and rather than fight it off, by attempting to engage in prostitutional aesthetics—politely put—and ingratiate myself with her, I went to eat the best fish and chips with mushy peas in Leeds. It was a celebratory dinner with my husband since I had been able to drive a van up to Leeds without having an accident and killing ourselves to bring a bunch of empty boxes to an exhibition.

A temporary thought came to my mind. Should I had made the aesthetics of power, exploitation, and abuse more palatable for a corporate audience? The British drill that art should be compliant with business practices had been able to insinuate, hissing like a snake, some doubts in my mind. They lasted a very short time. The time to leave the exhibition and reach the fish and chips joint.

As I continued to excavate files, while writing this chapter, I found some material in old Word documents or text files. The title of the works of art that went to Leeds was A-VOID-Travel, almost premonitory, and the installation was part of the exhibition New Directions: Art vs. Mainstream Visual Culture at the Cube Development in Leeds, UK. I guess at the time I was too much of a new direction for the curator. I remember laughing about that and about the need to avoid void travels… and void boxes.

After the Leeds experience, the works of art continued to exist and morphed into a website realized at the MediaLab at MIT. It was a project with which I wanted to provide a social interactive awareness. We had people interested in the project but there was not a crowd that was willing to explore the possibility of being enslaved in exchange for the remote opportunity of making one of their dreams a reality. I did not have a marketing department and was not able to generate as much hype as some of the social media companies that nowadays operate in the virtual for real gains.

Financial exploitation, labor practices for migrants, social justice, and lack of social upward mobility are themes that I continue to explore to this very day, even for Preferring Sinking to Surrender at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale.

On December 30, 2020, with Adobe’s announcement that Flash development was being stopped, I realized that Slaves4Sale.com as a work of art was gone. I had not made a copy, or if there is one in a folder somewhere I have not seen it this time around.

Image 2: Lanfranco Aceti, Slaves4Sale.com, 2003. An online interactive commodification experience. Cardboard boxes, Internet site, and Flash programming.

This work of art, in all of its manifestations and with all of its failures, consolidated my understanding of the nature of the digital and of human relations. It made clear the prostitutional nature not solely of the art world, but of the world in general, and the vulgar exercise of power which, from whatever group or tribe it may come, is always manifested as a form of assertion of dominance and enslavement.

A Not So Quick Panegyric

I have always hated panegyrics! They appear to me as a form of Hierarchical-Arse-Licking or more politely—for those hypocritically sensitive and humorless ethical souls that increasingly appear to populate the western world—as a way of ensuring that one could gain something through a form of exchange, barter, or prostitutional aesthetics, with the stronger party getting the better deal out of it. I first used Hierarchical-Arse-Licking on June 18, 2018, when I was invited to a two week Guggenheim sponsored workshop at Harvard University titled Beautiful Data: Telling Stories About Art with Open Collections, organized by the metaLAB.

I use the words new media’s prostitutional aesthetics to describe the selling of oneself—physically, emotionally, and/or intellectually—in the attempt to climb up the social ladder while making a new media spectacle of it and trying to monetize on it.

Rarely has it happened that I would find someone who would engage for the sheer pleasure of it on an art project, a piece of blue-sky research, or a randomly chosen idea just for the amusement of exploring possibilities without automatically thinking how to generate opportunities, how to monetize, or how to make the best out of a project for the benefit of one’s career, no matter who and what would get damaged in the process.

The exception to the rule is always out there, the difficulty is in detecting it, stumbling upon it, or finding it. I do not think that a methodology exists. At least I haven’t found it yet.

Most Anglo-Saxon professors will explain that success can be planned for and achieved by following their particular methodology. My experience is based on the contrary—the complexity of life cannot be reduced to a method or worse a template. Firstly because there are a variety of possible worlds and empires outside the remits of the artificial taxonomies of the Anglo-Saxon world and secondly because it would mean to suck out the beauty and complexity of life itself as well as the serendipity of emoting and thinking within the process. If the originality of an aesthetic and visual approach is to be found, it is certainly not through a template.

It was my good fortune to meet Professor Alessandro Melis, the curator of the Italian Pavilion for the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. The openness of his curating methodology, the interest in making sure that a project would flourish, or that an alternative methodology of process and progress could be enacted without too much institutional drama or controlling issues, was what made possible my work of art Preferring Sinking to Surrender. I am grateful to him for his curatorial approach which offered an incredibly large amount of leeway based on trust, but also to his intellectual input which allowed me to work with the notion of spandrels and take upon, once again, the idea of an organic methodology.

At the turning of the century, during my Ph.D. research at Central Saint Martins, College of Art and Design under the supervision of Prof. Malcolm Le Grice, the internationally renowned Fluxus artist and film director, and with the support of a great pedagogue, Ian Padgett, I explored the possibility of applying Jay Gould’s research to the fine arts. As opposed to his method of explaining evolutionary biology through architecture and art I used evolutionary biology to explain the complexity of an organic methodology applied to architecture and art. I developed a theory that through evolutionary biology could allow the exercise of freedom in the development of a more life-like aesthetic approach to artistic and architectural systems outside the Cartesian grid and in a state of nature.

At the time, I was particularly interested in new media art and its galloping and exciting developments, a phase of development of that particular art sector since then long gone. It made me consider the possibility for, if not of a digital renaissance, at least the flourishing of multiple original and globalized practices which could challenge authoritative models of curating and stifling aesthetic regimes. It was a hope which I looked at with a rather severe critical eye and healthy disenchantment, so much so that I wrote my concern in a paper on artistic practice using the analogy of ‘getting laid on the Procrustean bed’.

My fear was that experimentation from intermedia approaches to transdisciplinary frameworks would fail as much as the Avant-Garde had failed the moment in which was rendered ‘financially viable’ and had to be commodified to respond to the entertaining and pacifying needs of corporate aesthetics.

As a knee-jerk reaction to the convoluted and unusual approaches of new media artists in the 2010s, galleries and museums created ‘their brand’ of new media art and artists, pushing some of their traditional artists to transmute, and poached some of the more buyer-friendly aesthetic practices of younger, presentable, beautiful, sellable, and more pliable artists. These institutions and their new media whore accomplices developed forcefully aesthetic entertainment, making of it the major content produced by new media art, ever more inclined to follow fashion fads (aesthetic, technological, and social) and the news cycle in the attempt to grab the limelight in an Orwellian and Warholian modus. Of the artists who had contributed to the development of computer art, pioneered aesthetics, or pushed the envelope of new media’s social issues there were none, outside of the usual circle, circus, or enclosure of new media festivals. I felt increasingly detached from a system that was not just betraying the possibility of delivering change, but increasingly implementing aesthetic homogenization on a global scale, disempowering both artists and curators in favor of corporate assimilation. New media were and are the outlet through which aesthetic assimilation and diversity annihilation were being delivered.

In contrast to what I increasingly consider a regime of assimilation, it appears ever more precious the space and time afforded to me by Melis for my participation at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. Preferring Sinking to Surrender was a work of art realized through an interstitial space in which I could exist and do without a) the pressure to comply, be pliable, and having to whore myself out; b) the necessity to deliver pre-ordered and pre-digested content; and c) the obligation not to relate to the complexity of thirty thousand years of human history all the way back to its matriarchal roots.

It takes a great curator to deliver such an opportunity and I will be forever grateful to Melis for having provided it to me.

The Pandemic, Explosive Egos, and the Historicization of Idiocy

As the pandemic raged and I was creating my works of art for Preferring Sinking to Surrender to be exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale, I was hoping that new media, in all of its forms, would take a backseat and let the reality of personal interactions flourish. I guess my thinking differed from that of most people. It was instead a flurry of Zoom meetings, personal chats, and video calls (sexual and otherwise) for most of my friends. Some, though, had rediscovered the pleasure of reading poetry or philosophy, or baking, or some other hands-on activity which had been lost during previous years of ‘capitalistic enslavement’ as I called it.

I was dealing with family health issues during a pandemic in which nobody wanted to be caught within 100 miles of a hospital, and was luxuriating in the wonderfully free Italian public health system and some of the inefficiency that comes with free-of-charge services. I was back from the United States, so the fact that health care was free—although in the process of being increasingly privatized—was for me the highest sign of civilization a country could achieve.

Two years on, I find that the issues remain unchanged. New media art is not this purer and more ethical medium, as some of its practitioners would like us to believe. It is exactly like anything else that humans touch, filled with their abilities and faults, selfishness and generosity, but mostly selfishness.

Marshall McLuhan was absolutely on point arguing the issue of the ‘rear-view’ mirror. Unfortunately, in my experience, it is not solely an issue of interpretation of technology but also one of regional cultures. New media in Italy will be characterized by the behavioral systems of the Italians and filled, in Italy, with the same content that is on any other media. In the US, new media will be predominantly characterized by behaviors and cultural attitudes typical of the United States, and so forth for every nation or cultural group around the world. The concept of transmediation could not answer or face up to cultural specificities since its aim is not an approximation to the Parmenidian truth but the achievement of the best spot from which to gain the highest status maximizing aesthetic value for a corporate media product.

It is like a permanent rutting season played on multiple fields at the same time, or, like an Italian poet who achieved fame and success thanks to social media said, a place where to prostitute oneself. “Sex work can be many things. Phone sex, camming, porn, strippers, sugar babies, escorts, hookers, dommes — the categories and subcategories feel less like a list and more like an endless velvet labyrinth of sweat and nuance. It turns out, there are nearly as many ways to sell your own sexualized body as there are to have one.”[2]

Because sex work can be so many things, it is also a behavioral modus vivendi, one that can be combined with social media and new media practices. This gives us the opportunity for a definition of new media whores.

The new media whore is a person who constantly and shamelessly promotes their self without any consideration or respite for the audience with the ultimate goal of achieving celebrity status in their rutting field or community, no matter how small and insignificant that is.

New Media Whore, No More

As time went on and the pandemic continued, I found myself to be more and more repelled by new media and social media. In particular for social media, I am not interested in distant, superficial, and dysfunctional relations, based on constant self-censorship. Social media remains an intertwined aspect of self-promotion and at times an existential need for some artists and new media artists. I always wondered: where do they find the time?

The difference is, I guess, in the fact that being socially mediated is a lifestyle. For me being on social media is more of an obligation that I have towards the artists I curate and my own artworks. My presence is usually exhausted once the duty of advertising is accomplished. The rest (future developments, followers, etc.) doesn’t matter much, particularly when it is impossible to have deep and lasting exchanges or, as I have always known and always loathed, one has to self-censor.

I have never been much of a new media whore and don’t have the necessary enthusiasm to get all excited for a ‘new like’. I would prefer to meet in person and have a glass of wine and talk and discover absolute assonance or dissonance.

When producing a work of art, in my mind there is only one precondition and that is for it to be according to what I wish it to be. Or as closely as it can possibly be. The fact that some people may like what I do or even understand it, as happens sometimes, baffles, confuses, and moves me. But it mostly and profoundly moves me, making me happy in the fact that I have been able to generate assonance between two people that are total strangers. This approach is profoundly matriarchal in nature and completely out of touch with the current system of patriarchal capitalistic engagements in which art finds itself to be just another commodity.

As an artist, I am also riddled with doubt. Would engaging with the audience alter my thinking and would the artwork as a consequence be any different? Would it be not mine but theirs? Isn’t it hypocritical to appear to renounce authorship while still setting all the rules for engagements and outcomes, selling as interactive what are actually structured forms of interpassivity?

While I like the value of experimentation and play in the disruption of forms of authorship, I have discovered that there is something absolutely blissful in being in the studio by myself. Particularly if the studio is a vegetable patch, like the one I have used in the section Orthós for the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Image 3: Lanfranco Aceti, Is That Up in the Sky a Sign from the Left?, 2021. Arundo donax, red rice paper, and red thread. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

My studio since 2019, a vegetable patch, has allowed me to think, analyze, and reflect upon my understanding of what life is. I have had the opportunity to ponder life’s social, cultural, anthropological, and environmental inheritances.

This critical and artistic process, without the onslaught of new media, was less crowded, more silent, quieter, and introspective. Different sounds echoed through my days and different visuals from those sparked by the light of a computer screen stimulated my thinking.

My relational world had more to do with what was physically inherited than with what was electronically constructed. The relation to what-it-was and what-it-could-have-been became strident. Also, the what-it-could-have-been was dramatically different in the physical world than in the new media world.

A new media world where self-righteous click activists and armchair revolutionaries—created by the bourgeois laziness of American capitalism—went poof and disappeared, leaving the reality of the earth of the vegetable patch and concepts of dirt, being dirty, and stinking. To act required getting one’s hands dirty and demanded sweat from one’s brow while breaking ground under the scorching sun.

Image 4: Lanfranco Aceti, The Guardians, 2021. Arundo donax and ribbons. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

The entire world shifted as my understanding of change as being a personal and intimate journey developed. It was a physical change that could not be electronically mediated or that should not be transformed into an electronic fad. The physical world reminded me that change was made of resilience over long periods of time and not of short-term media opportunism. The time of new media, for me, was over. Or so I blissfully thought.

For two years I have had less and less screen time. My interest in screens diminished exponentially while my isolation facilitated the development of Preferring Sinking to Surrender—an opus magna—that I wouldn’t have been able to produce without silencing old and new media. (Please note in Latin it is opus magnum. I doubt anyone would have spotted this ‘error’, but in the odd case a Latinist stumbled upon this text, I thought they would appreciate an explanation for the violation of the rules of Latin and English grammar in favor of a matriarchal approach.)

My relational analysis focused more on what my relation to the world was and its multitude of other forms of life than to just the human beings that populated it. I had reduced the idea of society to its very basics, the reality of extended family limited to and inclusive of those people with whom there was assonance or at least a benevolent tolerance.

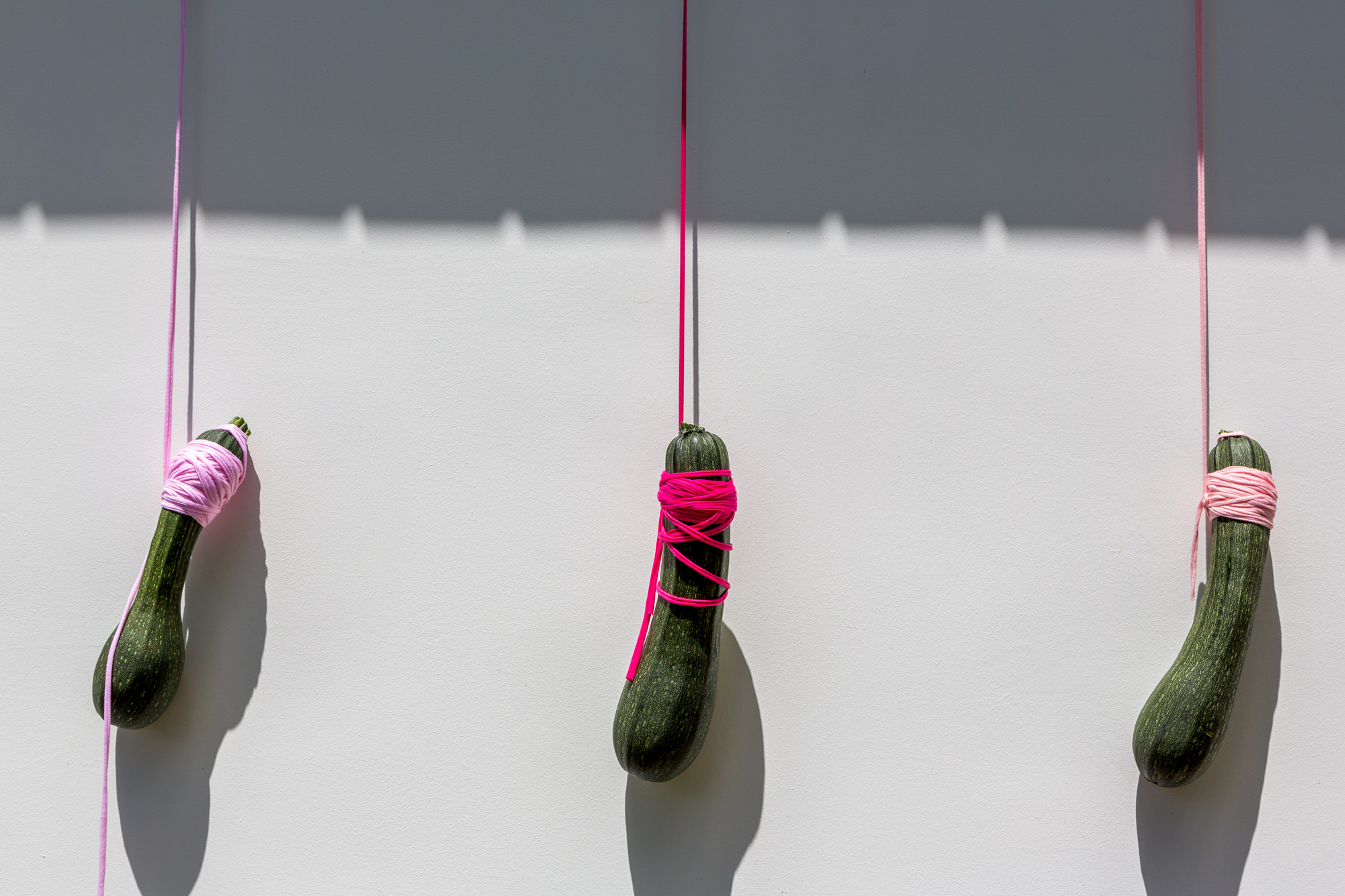

Image 5: Lanfranco Aceti, Hung, 2021. Zucchini and rope. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Matriarchalist theories and theology of liberation once again became my companions together with Parmenides’ philosophical genius. He didn’t make the Platonic error of compromising philosophical truths to justify the necessity of servitude of the truth to the nation-city at his time (the corporate nation-state now). I was a teenager again, working on what I liked most, thinking about what I wanted, and not having the external onus of having to filter it through the lens of the gatekeepers of capitalistic aesthetics and socio-political censorship.

This freedom, without the obligation of being a slave prostituted to new media, was intoxicating. The pandemic had given me freedom, much more than new media had ever done—something, albeit skeptically, that I had hoped new media would deliver. I was able to be what I wanted to be, an artist who celebrated the collapse of humanity thanks to the grandiosity of human stupidity. I could look passionately at human relations and relational aesthetics as a form of apotropaic magic that led me straight back to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s mythological realism and his anticipated collapse of postmodernity.

Relational Assonance

Two of the pioneers of new media, computer, and video art whose works of art I appreciate are Chuck Csuri and Malcolm Le Grice. While I curated a few exhibitions of Csuri’s work for Kasa Gallery in Istanbul and the Museum of Contemporary Cuts (MoCC), I have not yet had the pleasure of doing a retrospective of Le Grice’s video art.

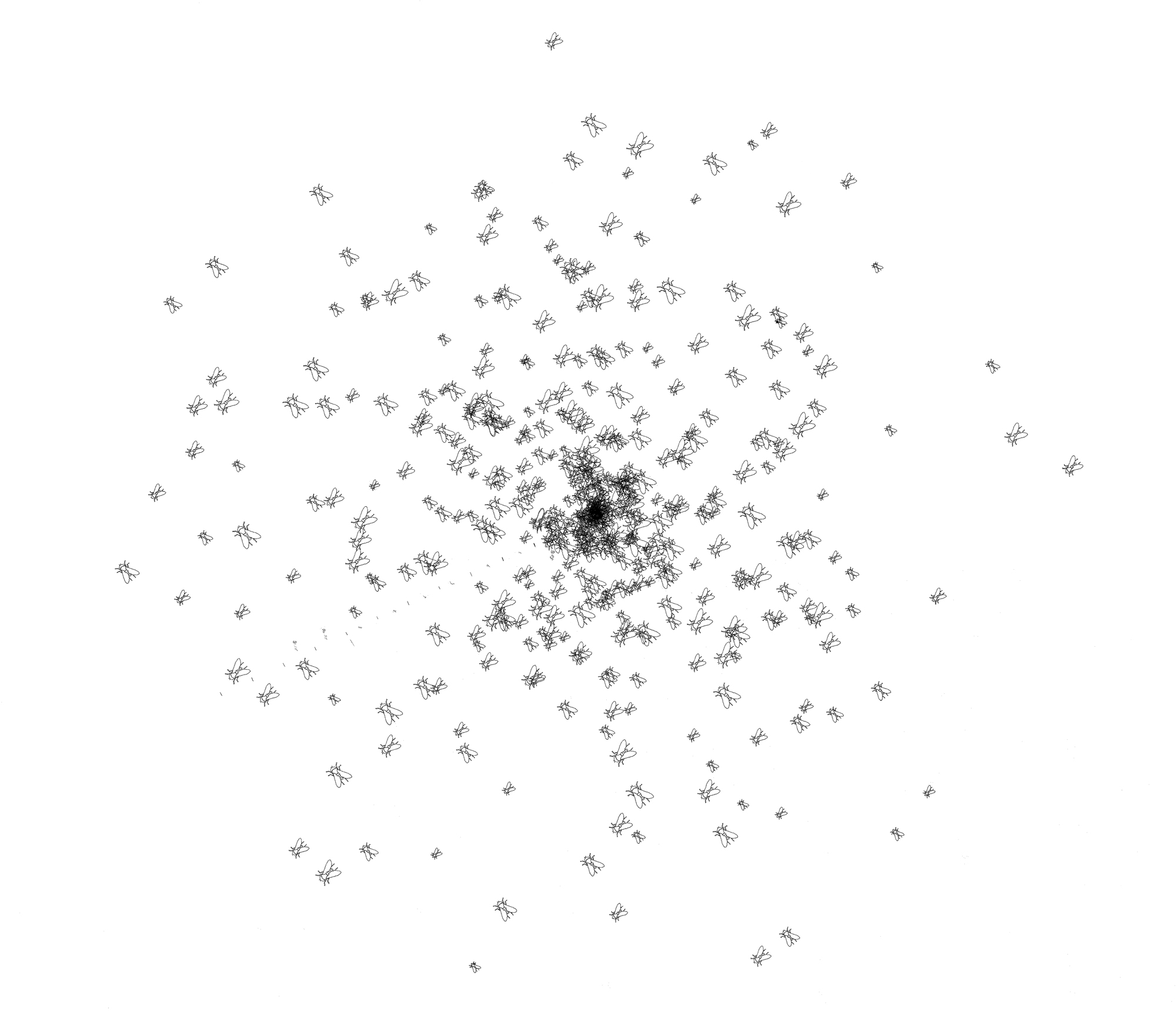

“A common housefly seemed to have a place in the context of an intelligence which will replace human beings. Possibly feeding off some residue left behind when the heat of the planet burns all the circuit boards.” (Chuck Csuri in communication with the author. April 24, 2018.)

Image 6: Charles ‘Chuck’ Csuri, Feeding Time, 1966. Plotter drawing in ink on paper. Dimensions: 36” x 31” (91.5 cm. x 78.75 cm.). IBM 7094 and CalComp 565 drum plotter. Copyright CsuriVision ltd. Courtesy of The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection.

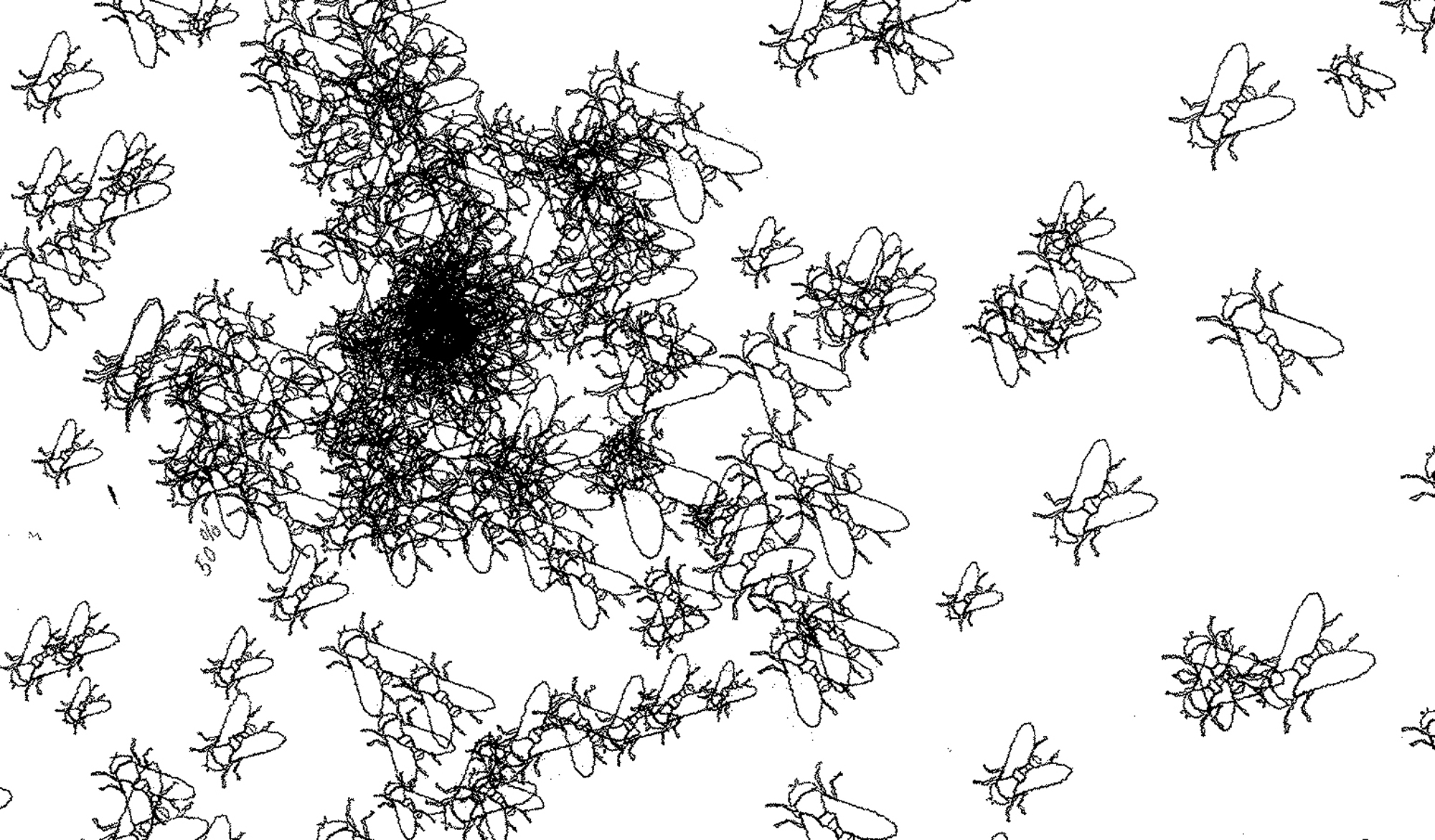

Image 7: Charles ‘Chuck’ Csuri, Feeding Time, 1966. Detail. Plotter drawing in ink on paper. Dimensions: 36” x 31” (91.5 cm. x 78.75 cm.). IBM 7094 and CalComp 565 drum plotter. Copyright CsuriVision ltd. Courtesy of The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection.

Every time I look at Csuri’s early works of art I am enthralled by the amount of tension that exists in them, both conceptually and in the realized drawings. I chose to show Feeding Time because it reminds me of the feeding frenzy of humanity. The flies appear to feed on the center of a black hole, converging on it, but also at the same time swarming out of it. The flies, one on top of the other, in some instances seem to cannibalize themselves and in others to be reproducing via meiosis. Or to be doing both simultaneously.

The flies enter and exit from the black hole within the white space of the page in a constant process that is based on the tension between center and periphery. Expansion and contraction are phases in a pulsating frenzy which seems to replicate the dreadful buzzing noise of the flies chomping away at everything and everyone, even at life itself.

The obsessive repetition of the flies in the drawing—as if they were the same creature only taken at different stages of existence—seems to portray the self-obsession with media self-observation and self-representation of contemporary post-postmodernity.

When I look at Csuri’s Feeding Time I imagine the black hole as the point from which all begins as a malignant cancer or as a necessary evil, or just as something that is and has no moral or ethical explanation, like primordial life is without excuses or need for justification. It also speaks of the point in which everything collapses into an eternal death always equal to itself, always in the process of replicating itself, and as a constant reminder of humanity’s selfish stupidity.

It is a drawing that balances the tensions between life and death, being and not being, as much of the early production of Csuri which addresses, both consciously and subconsciously, the profound meanings of life.

The minimalist appearance of the work of art disguises its complexity with the simplicity of its lines. The swarming of flies could be interpreted as the swarming of humanity with no other goal in sight than existing, both the flies and the humans ready to feed themselves on anything and everything, even on their very own selves.

Feeding Time offers the opportunity for reflection and critique of new media art via early computer art. The flies and the comparison I drew to human beings makes of Csuri’s drawing a critique of new media art that meshes with entertainment, boutade, shock, and technological primacy.

It is a critique of a world that is construed on self-obsessive new-media-whoring relations that are employed for the feeding of a never satiable self that is constantly seeking the magic formula for success. The necessity for a revolution of contexts, processes, and understandings as well as a dramatic alteration of the relations between humans and their contexts is not just necessary for a rethinking of what it means to be human but also overdue in order to prevent the ‘vegetable patch with its life forms’ from being transformed into a blank white page where everything has been fed upon by flies and humans alike.

There is no reason to continue doing things as they were done, since they do not necessarily approximate us to the truth of social relations, to the establishment of an assonance through which it is possible to recognize, acknowledge, and heal the suffering of others.

The world of technology becomes a field of self-authorized critique exercised through new media art either as a celebration of the transparency of the window or as a mirror to celebrate the righteousness of the viewer and the artist, both complicit in the establishment of a pernicious illusion of existence, action, and participation.

In both cases the art, if it can be called that, is in the technology and not in the status of human affairs. Plato’s reflection is pushed further into the cave; the illusory nature of art is reflected upon a technological mirror which reflects the illusion of an already illusory shadow, entrenching deeper than ever in the eyes and the brain the simulacrum of representation and further distancing the human gaze from a glimpse of the truth. Further and further away from the Goddess, we go.

The current patriarchal capitalistic structures and the functional critique of it, all together exist in a rather morbid perfunctory act that is a travesty of a technological illusion of Plato’s illusion of reality.

No Media Is the Message

As I was writing this chapter I stumbled upon something I had forgotten, an event I curated that was managed by John J. Francescutti at Birkbeck College on May 30, 2008. The title was No Media Is the Message and the guest speaker and artist was Le Grice. There was a screening of his video works, followed by a conversation on the role of new media and how it altered aesthetic approaches and the understanding of real and virtual processes.

The press release of the event stated: “The artist will also review his involvement with the digital through computer work and discuss the concepts of non-linearity, interactivity, the hybridity of production and distribution systems, including Internet distribution with YouTube.”

Image 8: Malcolm Le Grice, Digital Still Life, 1984-1986. 8 minutes, computer & video.

I worked with Le Grice, who as a Fluxus artist, a video maker, and an avant-garde artist, espoused an articulated view of new media. It corresponded to my theoretical approach which tried to find a balance between total acceptance and total rejection. At the time, I had already developed a critical understanding of new media since I had too much cynicism to believe in the propaganda of its salvific nature. I am not much of a joiner by nature and have always distrusted the announcements of opportunities for deliverance. Somehow, they never applied to me. Gender, race, and class were and are elements of exclusion and seclusion.

This was no more apparent to me than when I was in the United States at a farewell dinner for a curator who had been booted out due to internal political infighting. The quality of the work she had done bore no relation or relevance when it came to assessing her abilities. Race and gender played a hidden role. At the dinner I spoke of relational assonance—un moto dell’anima (a flight of the soul)—which I hastily and unfortunately translated as, on the fly directly from the Italian, a movement of the soul (un movimento dell’anima). If in Italian the word movement is often related to poetry, music, and higher purpose, unfortunately it immediately was pointed out in jest by a prominent member of the audience as soul-movement equaled bowel-movement. Perhaps there are things in common—in the end they are both processes—the former is a process toward higher aspirations, the latter a process for the production of existence’s remainder. One does not exist without the other, and I have always been in the trenches to ensure that the grittiness of life is represented in aesthetics. But this particular jest in relation to the moment spoke to me of ignorance, crassness, and an imperialistic vulgarity which should not be easily forgotten or underestimated. It reminded me of the literary character Parkhill in Martian Chronicles and the curse that knowledge brings with it. [3] It was then, as it is now, a sign of what is wrong with the patriarchal incapacity of emotively engaging. It is a sign of the impoverished life without poetry, magic, and myth that we lead thanks to the fascistic new world of new media’s technological imperialism. That episode also reminded me of Ray Bradbury’s character Spender, who describes the rise and fall of a civilization, the beauty and dread of life and death.

“A race builds itself for a million years, erects cities like those out there, does everything it can to give itself respect and beauty, and then it dies.” [4]

It is the grittiness of the unstoppable collapse and transformation through rotting that I am reminded of by Le Grice’s Digital Still Life. It is the permanence of a condition that even the digital, despite its hype, has not been able to cancel.

As screen time re-enters my life because of post-production work and the necessity to write this chapter, I realize that hybridization of reality has taken place. It is no longer a priority to invest in creating a natural world in the ‘mirror’ of the virtual, but rather to embed the technological in the natural, completing that Cartesian logical grid upon what is considered and is being rendered illogical and unnatural. The very nature of nature is now unnatural and irrational since it has to bend to the construct of a capital accumulation with no other purpose or higher goal than the definition of the ego through accumulation itself.

This is the reason why I have chosen the works of art by Csuri and Le Grice. They both speak of life and death, of a process of existence as appearance and disappearance, and of the unfolding of time and history. Ultimately, it is a socio-political understanding of our reality through art that bypasses the personal and the screen to become a terrorizing look upon a universal condition within which and from which we cannot escape, even through the accumulation of capital and the severing of relations. They speak of a bowel-movement and a flight-of-the-soul which although separate are conjoined processes and although contradicting each other as antithetical propositions both exist and are true in the same sense, in the same time, and in the same space.

The law of non-contradiction did not apply in the state of nature, but it is a fundamental rule and applies in the Cartesian world. The strict logic of the Cartesian world exists as the fault upon which is built an ever more homogeneous world that is destined to end blinded by its certainties and technology. Le Grice’s Digital Still Life violates that rule by creating a still life that is about a process of rotting that does not stay still and that speaks of a process of dying that is constant transformation, constant death, and constant life even in the digital. Le Grice uses new media to remind us of context, history, and relations, even when the medium tries to sever them, hide them, and render them invisible.

This process of constant transformation came back to my mind once again when my laptop, after 15 minutes in the sun in the South of Italy, was frying during a Zoom meeting for the Venice Architecture Biennale. The fragility of the electronic medium brought to mind the conference Stone and Papyrus, Storage and Transmission chaired by William Uricchio and Henry Jenkins at Comparative Media Studies at MIT. It was at this conference that I presented a paper titled When Art Creation Is Ephemeral: Digital Migrations of Contemporary Time-Based Media and Obsolete Space-Based Media. As I sifted through the internet searching for this paper, I stumbled upon another presentation titled Beyond Mummification and Resurrection in Digital Media, which I gave for mundanetechnologies.com at Lancaster University. These papers analyzed issues of preservation of digital media art and the imposed obligation to transcend the ephemerality of digital media to realize a material object to be permanently exhibited and sold. The chasm between the solidity and permanence of the stone and the intangibility and ephemerality of the digital remains. The stone, nevertheless, had already come back with its despotic materiality in my artistic practice. It appeared that there were no new media in sight. The process, the bowel movement, and the flight of the soul that made possible my works of art were a reflection of intermedia Fluxus theories, of Higgins’ interstitial search for innovation, experimentation, and survival. The works of art embodied Pasolini’s disdain for the destruction to come out of post-modernity, American technological imperialism, and fascistic ideas of progress as a Cartesian dogma above all other cultures and all other traditions. They also embodied my disdain for that fascism of the right and of the left which operates under different names but that keeps firmly in place the walls of segregation and pseudo-cultural wars.

As the laptop fried and died, at the end of the Zoom call, I didn’t feel like attempting to save something that couldn’t cope with physical reality. I realized something that I had known all along; a revolution would not come from the inside through a fancy technological tool but rather through a piece of wood that could be used to plant or to gouge eyes out.

Image 9: Lanfranco Aceti, Up Yours, 2021. Wood and pink nail polish. Photograph of the performance. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

That piece of wood had thirty thousand years of history that no fascism could obliterate and that no patriarchal structure could silence. The matriarchal values were still there, operating through my work in alliance with and fighting against new media in a contradictory state of nature. They were finding new ways of emerging through a revolution that, like a language-virus, would come out from the periphery of the technological empire and not through new media whoring.

Image 10: Lanfranco Aceti, Readying to Gouge Your Eyes Out, 2021. Wood and pink nail polish. Photograph and digital composition of the performance. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Conclusions at The Ending of the End

The Ending of the End is the final section of Preferring Sinking to Surrender, one of ten sections. It is how I wish to close this chapter since the end of something implies the beginning of something new.

Although the hollowed-out landscape I have presented of media relations of undying dead is bleak like Csuri’s white page or devastatingly corrosive like Le Grice’s rotting digital fruits, there is the hope in Preferring Sinking to Surrender that the current celebration of prostitutional aesthetics and blank relational gazes onto the world might not survive. There is the inherited possibility that the materiality of the stone, wood, and life itself might oblige humanity to move away from the Baudrillardian simulacra of socially mediated contemporary politics and life. Relations might be rediscovered not as forms of selfish prostitution of the self but as a symbiotic exchanges that sublimate and celebrate life itself. The age of new media whores might come to an end, pushed aside by life’s materiality. If not soon then at some point life might make space for the development of something different.

New technologies might arrive, produced perhaps not by humans but by other species, in a world that has been transformed into something else. Or perhaps not. Or the contradictions of the natural and technological might coexist at the same time and in the same space. Whatever it is that might emerge my hope remains that it will allow for a matriarchal cultural revolution, offering humanity the possibility of existing in a natural state in which being human will be defined, as in ancient pre-Roman times during the cult of the Goddess or even through contemporary matriarchal technological means, by one’s symbiotic relational assonance to the world and the living beings in it.

How and if we will ever reach that status is uncertain. The propaganda of the western world with its faith in science and technology as exploitative tools for the very rich is unfortunately supported by the very masses who are enslaved to these processes.

ENDNOTES

[1] Urban Dictionary, https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Media%20Whore&page=2 (accessed November 10, 2021).

[2] Clementine Von Radics foreword to A Whore’s Manifesto: An Anthology of Writing and Artwork by Sex Workers, edited by Kay Kassirer (Portland, OR: Thorntree Press, 2019).

[3] “The next afternoon Parkhill did some target practice in one of the dead cities, shooting out the crystal windows and blowing the tops off the fragile towers. The captain caught Parkhill and knocked his teeth out.” Ray Bradbury, Martian Chronicles (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 95.

[4] Ray Bradbury, Martian Chronicles (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 66.

IMAGES

Image Cover: Lanfranco Aceti, The Box Returns, 2022. Cardboard box (realized in 1998 and returned from MoMA in 1999; dimensions: 23 cm. x 28.8 cm. x 13.5 cm.) and undeclared contents. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. Black and white.

Image 1: Lanfranco Aceti, The Box Returns, 2022. Cardboard box (realized in 1998 and returned from MoMA in 1999; dimensions: 23 cm. x 28.8 cm. x 13.5 cm.) and undeclared contents. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm.

Image 2: Lanfranco Aceti, Slaves4Sale.com, 2003. An online interactive commodification experience. Cardboard boxes, Internet site, and Flash programming.

Image 3: Lanfranco Aceti, Is That Up in the Sky a Sign from the Left?, 2021. Arundo donax, red rice paper, and red thread. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Image 4: Lanfranco Aceti, The Guardians, 2021. Arundo donax and ribbons. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Image 5: Lanfranco Aceti, Hung, 2021. Zucchini and rope. Sculpture, installation, and performance. Photographic print. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Image 6: Charles ‘Chuck’ Csuri, Feeding Time, 1966. Plotter drawing in ink on paper. Dimensions: 36” x 31” (91.5 cm. x 78.75 cm.). IBM 7094 and CalComp 565 drum plotter. Copyright CsuriVision ltd. Courtesy of The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection.

Image 7: Charles ‘Chuck’ Csuri, Feeding Time, 1966. Detail. Plotter drawing in ink on paper. Dimensions: 36” x 31” (91.5 cm. x 78.75 cm.). IBM 7094 and CalComp 565 drum plotter. Copyright CsuriVision ltd. Courtesy of The Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection.

Image 8: Malcolm Le Grice, Digital Still Life, 1984-1986. 8 minutes, computer & video.

Image 9: Lanfranco Aceti, Up Yours, 2021. Wood and pink nail polish. Photograph of the performance. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

Image 10: Lanfranco Aceti, Readying to Gouge Your Eyes Out, 2021. Wood and pink nail polish. Photograph and digital composition of the performance. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm. 17th Venice Architecture Biennale. Curator: Alessandro Melis.

CITATION

CHICAGO MANUAL OF STYLE

A version of this essay is scheduled for publication.

Lanfranco Aceti, “Relational Aesthetics: Onto a World of Undying Dead,” in Encyclopedia of New Media Art, ed. Paul Thomas (Bloomsbury, FORTHCOMING 2024).

.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With Gratitude

I wish to thank Professor Paul Thomas for inviting me to contribute this essay and for his patience with a reluctant writer. In an alternative format, this work will be featured in an upcoming book by Bloomsbury as part of the Encyclopedia of New Media Art.