“People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them. […] the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly. ”

James Baldwin

ABSTRACT

This essay critically examines the material conditions faced by immigrants in the United States, emphasizing how poverty, isolation, and systemic neglect shape their survival strategies. Immigrant populations, often forced into abject living conditions with limited resources, adopt dietary practices that reflect both their marginalized status and their resilience. Two central issues frame this analysis: First, the ethical responsibility of the host nation to provide adequate support to immigrants, thus preventing survival strategies reminiscent of historical crises. Second, the political manipulation of immigrant survival practices, with both the political left and right instrumentalizing these conditions—either portraying them as symbols of degradation and victimization, or as existential threats to national identity and cultural norms.

This debate exposes deep hypocrisies within American cultural discourse, particularly among the descendants of earlier immigrant groups. Many who express moral outrage at the idea of consuming pets in times of desperation are themselves descendants of individuals who, in similarly harsh circumstances, engaged in taboo survival practices. These historical parallels offer a critical lens through which to interrogate the contradictions embedded in American cultural identity—a society that outwardly celebrates inclusion and progress, yet continues to reinforce racialized and class-based hierarchies by manipulating survival imagery and stories for political gain.

The essay calls for a fundamental reorientation of the discourse surrounding immigration, food, and cultural identity, urging a shift beyond sensationalist narratives that exploit immigrant suffering for ideological purposes. Instead, it advocates for a rigorous engagement with the material realities faced by both immigrant communities and the local populations morally, though not always voluntarily, tasked with receiving them. Recognizing that such “welcoming” is often forced upon local populations, the analysis underscores the urgency of humane and equitable policies that respect the dignity and survival of all individuals, regardless of their cultural or dietary practices. In doing so, the essay challenges reductive and xenophobic political and media rhetoric, advocating for an ethical recalibration that acknowledges the shared vulnerabilities and resilience of both immigrants and local communities in the face of inadequate systemic support.

KEYWORDS: Immigration, Food Politics, Survival Strategies, Cultural Hypocrisy, Political Rhetoric, Body Politics, Pet Consumption, American Cultural Identity, Ethical Responsibility

Entrée to the Civilized Food of the American Dream

The current American immigration debate is deeply enmeshed in a complex web of food, culture, and body politics, where sensationalist rhetoric often overshadows the material realities of migrant survival. A recent controversy from the Harris versus Trump debate, during which former President Trump made unsubstantiated claims about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, allegedly consuming pets such as cats and dogs, has reignited cultural anxieties surrounding immigration and survival practices. [1] Although media outlets quickly refuted these claims as baseless [2] the incident speaks to a broader societal unease. The rush to dismiss such claims without fully examining the conditions these communities face highlights a larger, more insidious issue: both sides of the political spectrum exploit immigrant populations and local citizens for ideological gain, while failing to address the real struggles of these marginalized groups.

The role of the U.S. in the systemic devastation of Haiti since its occupation in 1915 is frequently overlooked, as are the moral obligations for reparations to a country crippled by over a century of predatory capitalism. [3] Haitian immigrants do not come from a ‘shithole country,’ but from a country that has been transformed into one by the exploitative U.S. policies, which favored economic pillage and political control over Haiti and other nations in Central and Latin America and by a media representation of the trauma and alienation of the ‘other’ as ulterior form of exploitation for media and political gaines. [4]

Throughout human history, the consumption of animals traditionally regarded as pets or culturally taboo has emerged as a survival strategy during periods of extreme hardship. This practice is not unique to any specific group of immigrants—whether or not they have engaged in such behaviors—but is a recurring response to conditions of deprivation. The broader anthropological and historical record attests to this phenomenon, which transcends specific cultural or temporal boundaries. For example, during periods of starvation, Native American tribes, such as the Sioux [5] and Pawnee, [6] were known to consume dogs both as part of certain cultural rituals and as a necessary response to environmental stress, exacerbated by extermination policies aimed at their populations and their food sources. [7] These practices, far from being mere cultural curiosities, are emblematic of the extreme measures taken in response to colonial aggression, conflicts, environmental degradation, and a disrupted ecosystem. Anthropological studies reveal that such acts were often a last resort, deeply tied to cultural and spiritual meanings, and not merely acts of consumption but also of survival and resistance to extermination.

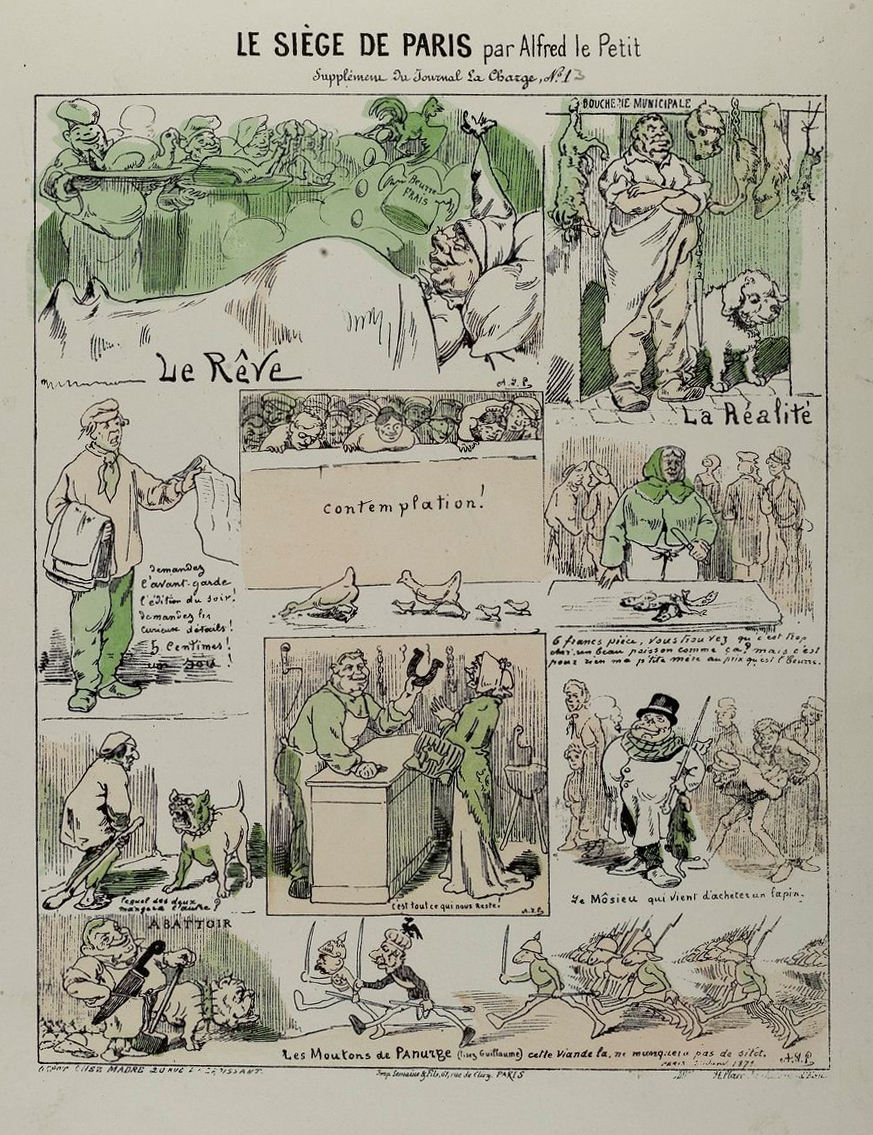

Similarly, impoverished immigrant groups from Europe to the U.S. have historically resorted to consuming unconventional or non-traditional animals during times of famine or siege, underscoring the lengths to which populations must go when faced with the threat of starvation. A particularly vivid example of such conditions can be observed during the siege of Paris, from September 19, 1870, to January 28, 1871, when Parisians, subjected to intense food shortages, were forced to consume cats, dogs, and even rats. As documented in satirical illustrations of the time, butchers were represented offering pets and rodents as alternatives to the increasingly rare and expensive traditional sources of meat. One such illustration poignantly contrasts the dream of abundance—depicting chefs presenting meat dishes and butter with eggs—with the grim reality of a butcher selling a cat, a dog’s head, a horse’s foot, and a rat, while offering a horseshoe as a reminder that nothing edible remained. This surreal juxtaposition not only highlights the desperation of the besieged population but also points to the resilience and adaptability of communities in times of crisis, where even the most culturally taboo animals became sources of sustenance. This example from Paris parallels survival strategies found among marginalized immigrant populations globally, offering a compelling reflection on the intersection of necessity, culture, and food. [8] Furthermore, what or who is devoured as a survival tactic extends into a broader, more existential dilemma: the fear of becoming the one who is devoured. In such precarious situations, the act of devouring becomes both a literal and symbolic act of identity assimilation—an attempt to resist becoming the vulnerable, consumed ‘other.’ This tension echoes throughout history, where acts of literal consumption intersect with spiritual and ideological conflicts. For example, Jean de Léry’s Histoire d’un voyage draws a parallel between cases of cannibalism in France and the theological battle over transubstantiation. Léry provocatively suggested that Catholics who partook in the Eucharist, consuming the symbolic flesh of Christ, were not dissimilar to those who brutally consumed the bodies of Protestant victims during the religious wars of the time. Such comparisons highlight how acts of devouring are imbued with deeper layers of meaning—intertwining survival, religious identity, and political power. [9]

Image 1: La siège de Paris par Alfred le Petit. Supplément du Journal La Charge N°. 13. Heidelberg University Library.

Image 2: La siège de Paris par Alfred le Petit. Supplément du Journal La Charge N°. 13. Detail. Heidelberg University Library.

The tension between belonging and exclusion in times of crisis often determines the fluidity of food taboos, which are deeply contextual and subject to change based on circumstances. As historical examples from the 20th century illustrate, the consumption of animals typically considered taboo, such as cats, were more common in communities facing severe deprivation, such as during the Spanish Civil War and World War II. Anthropologist F. Xavier Medina explores this phenomenon in his research on survival food practices in Spain, highlighting the uneasy balance between disgust and necessity. As deprivation affected entire communities, the imperative to survive transcended deeply ingrained social taboos, reflecting the uneasy position of ‘others’ within the group—those who suffered most but remained a part of it.

Medina recounts a particularly telling anecdote from a family recipe book, which includes instructions for cooking “Cat Stew.”

“Among the many recipes noted down in the book, of which there were probably more than forty, one in particular caught my attention: its title was ‘Cat Stew’. […] Even so, she was not aware of having ever eaten cat meat (the very idea disgusted her, as she remarked on that occasion), neither prepared according to that recipe nor cooked in any other way, and she did not know how the recipe had ended up in the family cookery book. Yet, when asked whether she knew of any cases of other families or people who had consumed this meat, she gave a different answer: she had heard of people actually eating cat meat, especially during the war years, although she herself had not witnessed it.” [10]

This account corroborates the adaptability of food practices under duress, and how survival can override cultural boundaries and identity markers. Italians, particularly from the northern regions like Vicenza, were known to consume cats and are, even to this day, colloquially referred to as Vicentini magnagati (Vicentine cat-eaters). The Italians have long-standing recipes for cooking cats, often prepared in dishes like gatto alla vicentina, gatto in umido, or gatto in salmì, especially during times of severe scarcity—historically and into the early 20th century. During the World Wars, this practice became widespread throughout Italy, from the northern regions to the southern tip of the peninsula. What might seem shocking to modern audiences or even contemporary Italians was a stark reality in the past, when survival trumped culinary preferences. For instance, in 2010, a prominent Italian TV chef was removed from his program after he casually mentioned the consumption of cats during the 1930s and 1940s—a practice once rooted in necessity but now taboo to the broader Italian public. [11] This incident reveals how perceptions of what constitutes food can shift dramatically over time, influenced by both cultural identity and changing social norms. In some cases, animals that were once eaten for survival can later become untouchable, only to be re-evaluated and even transformed into regional delicacies as their historical context fades. This reflects a broader phenomenon observed in marginalized or struggling communities worldwide, where survival pressures force people to adapt and consume what might otherwise be considered taboo animals. The consumption of such animals illustrates the resilience and adaptability of food cultures, shaped by the demands of extreme economic or environmental circumstances. [12]

In Switzerland, too, cat meat was once considered a meal worthy of local pride, though such food practices have largely disappeared in contemporary times. [13] These examples demonstrate how survival narratives—once framed as pragmatic responses to deprivation— over time have evolved into consolidated gourmet dishes to share with friends. [14] However, they often clash with modern cultural sensibilities, which may label such practices as either primitive or grotesque, depending on political or social agendas. These fading historical survival strategies, in France, Italy, and Switzerland, either as inherited cultural remnants or reflective of the broader reality of marginalized groups, demonstrate the struggles of communities that, abandoned by both the state and society, must rely on available resources for sustenance.

This examination highlights a recurring theme: the boundaries of what is considered acceptable food are often shaped by social, economic, and environmental factors. In many cases, what may be perceived as taboo or grotesque in times of abundance becomes a necessity in periods of scarcity. The examples from Native American tribes and impoverished European communities reveal how survival tactics adapt to the pressures of deprivation, illustrating the fragile line between cultural traditions and the harsh realities of survival.

In this context, it’s essential to consider that food taboos are often culturally constructed and flexible, depending on material conditions. This practice, though nearly vanished today, brings back to the fore the importance of food in forming identity, even in situations of deprivation, and reveals how communities have historically navigated survival through culinary adaptation.

The debate surrounding former President Trump’s claim that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, were eating pets such as cats or dogs exemplifies a broader issue intersecting food, culture, and body politics within American immigration discourse. The media—and by extension, the social media community—quickly shifted the conversation away from addressing the broader humanitarian crisis at play in Haiti and for the Haitian migrant community to a matter of internal politics focused on outrage. The outrage of the right for the possibility that someone might be devouring the middle class American Dream and the outrage of the left for the possibility that the undermining of the noble savage might undermine the American Dream of whitewashed inclusiveness for different races and identities. This shift also diverted attention from the real and urgent tensions between incoming immigrant populations and already-strained local communities. The problem, then, is not whether such claims can be proven or disproven but how this rhetoric obscures deeper systemic issues. In this framing, immigrants become pawns in a political theater of ideological manipulation, where the focus on sensational claims overshadows their real circumstances and survival strategies, while local communities—also facing resource scarcity—are often left without adequate support.

The logistical challenges of verifying such isolated claims make it unlikely that any concrete evidence could emerge from Springfield to confirm instances of pet consumption, especially given the cultural taboos surrounding such practices. Even if incidents of killing, butchering, and cooking pets did occur, they would likely remain hidden from view. However, this lack of visibility does not serve as definitive proof that these events never happen. Comparable incidents have been documented in other parts of the world, particularly in situations marked by extreme poverty and social marginalization. For instance, a recent video from Italy shows an immigrant from the Ivory Coast, destitute and without access to food, roasting a cat over an open fire near the busy train station of Campiglia Marittima. [15] (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-20B08OEjrQ) The outrage sparked by the video reflects the cultural dissonance between societal norms governing food practices in stable, privileged contexts and the survival strategies employed by marginalized populations facing desperation. This incident compels a reevaluation of how societies perceive food consumption, highlighting the disparity between culturally constructed ideas of what constitutes acceptable food and the harsh realities faced by those on the margins.

Image 3: Lanfranco Aceti, Meow, Meow, Meow, 2024. Digital still from video. From the series: Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

For Native American tribes as well as migrants to the U.S., food practices were not merely about survival but were deeply intertwined with the broader context of colonial extermination policies, merging into the mainstream concept of American whiteness, [16] and erasing of original identities as acceptance of the abundance and superiority—superior abundance—of the cornucopia [17] of the American dream. When Benjamin Franklin wrote “why should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion” [18] entire communities, both native and immigrants, had already faced systematic efforts to eradicate their populations and ways of life in order to disappear from or seamlessly blend into the “complexion” of the American Dream.

In contrast to the Native Americans, for the European settlers and frontiersmen who traversed and colonized the vast expanse of North America—often referred to as pioneers or homesteaders—the act of consuming food and local animals became part of the larger project of conquest. After shaky beginnings in which the surviving people of the colonies had to be forbidden to eat farm animals and dogs, [19] the settlers engaged in the wholesale exploitation of what they perceived to be an inexhaustible supply of animal resources. [20] This consumption was emblematic of their belief in the myth of an endless frontier, where nature was seemingly abundant and available for the taking, reinforcing the ideology of Manifest Destiny. [21]

While in regions around the globe, such as Europe and East Asia, the consumption of taboo foods, like cats and dogs, has been part of longstanding culinary traditions shaped by cultural, historical, and environmental factors, the U.S. settler’s approach to food was distinct in its focus on abundance and expansion. Their consumption patterns reflected a mythology of limitless resources, feeding a narrative of dominion over the land and its creatures. This mythology contrasted sharply with the survival strategies of Indigenous populations, who, facing environmental and economic collapse, had to make use of whatever resources were available, including dogs, as a response to their systemic marginalization. In the settler’s view, the seemingly infinite supply of natural resources validated their right to consume and conquer, casting Indigenous practices as primitive while they themselves engaged in an unsustainable extraction of the land’s bounty.

In Italy, as across the entirety of Europe, over two millennia and during the early 20th century and both World Wars, the focus was never on abundance but resourcefulness in the management of food scarcity. Poverty-stricken communities the world over resorted to incorporating offal [22] and taboo animals into their diets out of sheer necessity. Over time, these survival tactics evolved into culinary preferences, with some dishes becoming regional specialties. Even today, older generations across Italy recall recipes passed down from eras of deprivation. However, as modernization and economic recovery have taken hold, these practices have largely faded away.

Yet, in the process of modernization, Italians have not merely eliminated survival-based practices but uprooted entire culinary traditions: famous are numerous recipes made from the quinto quarto which involves cooking kidneys, liver, tail, snout, ears, brains, tripe, blood, heart, and everything else, including genitalia. [23] These recipes with offals remain foreign to the mainstream American representation of local and international cuisines. [24] The increasing McDonaldization of Italian food culture—driven by mass production, corporate interests, and an American imperialistic homogenization of taste—has replaced these authentic, locally grounded traditions with American standardized fare of mass food production, even if they are considered in Italy disgusting and unethical practices. [25] The food mass production is threatening to reduce the richness of Italy’s culinary heritage to the lows of fast-food culture. There is an entire rustic tradition of agricultural homesteads and food production for household consumption that have been sidelined by American social media representation of food, EU legislation, and local laws which tend to favor large corporate interests and American cultural and food imperialism. This is a shift that I wanted to document with an artwork using an almost forgotten recipe made with chicken blood and entrails.

Image 4: Lanfranco Aceti, Finally, I Got Casted, 2019. From the series Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

Therefore, the cultural history of survival food is not confined to the infinite exploitation of the land, but is also signposted by dramatic economic, social, and geopolitical shifts which, particularly in the U.S., over almost a couple of centuries have thrown off the bandwagon of the American Dream tens of million of people. During the Great Depression in the United States, many impoverished Americans turned to animals like squirrels, opossums, raccoons, and even rats—species not typically considered part of the mainstream diet. Such practices reveal a pattern in which communities on the margins of society, facing systemic neglect and deprivation, adapt their food consumption habits in ways that defy normative cultural expectations. In many cases, the act of consuming what is considered taboo by the dominant culture reflects not just hunger but also a negotiation of cultural identity, belonging, and survival.

The media’s swift dismissal of Trump’s claims as baseless ignores these historical precedents, revealing a deeper reluctance to engage with the uncomfortable realities of poverty and food insecurity that many immigrant communities face, even in the land of the American Dream, and even if they are not migrants but American citizens. It is a weaponization of food which, at this particular moment in time, shows an ever larger divide between the political left and right in the U.S.

The populist right and moralistic left employ contrasting narratives when addressing the complexities of immigration in the U.S., particularly in relation to the American Dream. On one side, the populist right tends to frame the discourse through fear and protectionism, warning U.S. citizens that their homes, jobs, and way of life—their “American Dream”—are under threat from immigrants, depicted as invaders, barbarians, or pet-eaters. This rhetoric taps into anxieties about cultural and economic displacement, painting immigrants as outsiders who will undermine and consume the prosperity of the native-born population.

In contrast, the moralistic left often speaks to more affluent urban enclaves, offering a vision of multiculturalism that celebrates the success stories of immigrant communities—those who have managed to assimilate or “whitewash” themselves to fit into the dominant cultural norms. However, this approach risks idealizing certain immigrant groups while ignoring the systemic barriers others face. It suggests that the American Dream is attainable, but primarily for those who have navigated the process of conforming to a WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) ideal, rather than preserving and integrating their own cultural identity. [26]

The unfolding of the media narrative on the Haitian immigrants in Springfield is a signal of a malaise which should bring attention to the ‘“deplorables” or “pariah” of society, [27] not to deride them but to show them compassion and helping them. The relocation en masse to small, under-resourced towns, where people are left to fend for themselves might generate the conditions where such survival strategies could become necessary. Springfield, with a population of 60,000, suddenly found itself hosting between 12,000 to 20,000 immigrants, [28] many of whom lacked sufficient resources, infrastructure, or social support. This overwhelming influx of people placed a significant burden on a community ill-prepared to manage the humanitarian crisis. Instead of focusing on the very real concerns of migrant neglect and inadequate policy responses together with the crisis of local struggling lower and middle classes, American media diverted attention to the spectacle of Trump’s unverified comments, feeding into a narrative of partisan outrage rather than substantive critique.

The broader question of immigrant survival in America has historical roots in the ways that certain communities are systematically neglected. While the right-wing media often frames immigrants as a threat to American cultural values, the left is not without fault. Policies under Democratic leadership have frequently resulted in the abandonment of large migrant populations with little to no planning for their welcoming, integration, or welfare. Local communities, of earlier migrants, already stretched thin, are left grappling with the influx of people, exacerbating tensions between local populations and newcomers. Rather than addressing these structural failings, both political parties continue to weaponize immigration for their own rhetorical purposes at times even directly pitting one community against the other naming one or the other as better representation of the integration and assimilation into the American Dream.

This narrative is part of a broader cultural hypocrisy in America, where descendants of earlier waves of immigrants—many of whom also faced cultural stigma and food insecurity—now participate in the demonization of more recent arrivals. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian and Irish immigrants were often vilified for their dietary habits, which were seen as foreign and unclean by the dominant Anglo-American population. Asian populations suffered the same accusations as dog eaters showing a pattern of political and media demonization which trickled in the social context of everyday representation of migrants. Today, similar cultural anxieties are projected onto Haitians, Central Americans, Latin Americans, and Africans migrants, whose food practices are scrutinized as markers of their supposed incompatibility with American values. This cycle of scapegoating new immigrant groups, while ignoring the structural conditions that produce their food insecurity, reflects a persistent unwillingness to engage with the realities of poverty and survival in America. [29] American society continues to present itself as a land of plenty, when the reality has changed for many existing communities in one of dire living and for many incoming communities as one of labor exploitation.

“[U]nless the New Comers have more Industry and Frugality than the Natives, and then they will provide more Subsistence, and increase in the Country; but they will gradually eat the Natives out” [30] or their family pets.

Ultimately, the fixation on the political theater whether or not immigrants might eat pets serves to distract from the unwillingness of the U.S. government and its political parties to provide adequate support for those it relocates and for the communities that welcome them who are left to fend for themselves in an economically and socially hostile environment, with little access to resources or support. The media’s eagerness to dismiss Trump’s comments, while politically convenient, does little to address the broader humanitarian crisis, but favors the polarization of the citizen themselves divided between rich and poor, commendable and deplorable. [31] By reducing the debate to a matter of debunking unsubstantiated claims, most U.S. media outlets missed an opportunity to engage with the larger systemic problems that leave immigrant communities in a state of precarity, retracing political responsibilities for failed policies towards migrants as well as locals, both sharing and experiencing the crisis of the American Dream. This failure speaks to a larger cultural and political hypocrisy—one that transcends partisan lines and reflects the systemic abandonment of the most vulnerable populations in American society, migrant or local that they may be. The fear of the “Natives” [32] being eaten out, as Benjamin Franklin puts it, should not be about the incoming waves of migrants, if the mythology of American abundance still holds, but about the conditions of entry into, sub-existence in, and exploitation by the American Dream, which remains unchallenged, despite being the reason why both the average American citizens and the immigrants are condemned to exist in poverty and to eat each other out.

Image 5: Lanfranco Aceti, Rehearsing, 2019. From the series Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

Eating The Roadkills of the American Dream

Accusations surrounding the consumption of pets, or the denial of such practices within immigrant communities, serve as mechanisms of cultural erasure. In the U.S., immigrants are subjected to external pressures that define their identities through rigid ideological frameworks, confining them to predetermined cultural roles. This process erases the complexities of immigrant identities and denies the fluidity of cultural expression, particularly in food traditions. The lens through which eating taboo foods and committing acts of cannibalism can be acceptable is only through the civilized gaze of American imperialism and its cultural narratives, may they be literary, filmic, theatrical or televised. [33]

Oral histories of discrimination, based on food habits, are passed down through immigrant communities but are often excluded from written documentation, leaving gaps in the historical narrative. These stories, while difficult to trace in formal records, are valid and reflect a nuanced intersection of immigrant experiences with mainstream American culture. The hybridized cuisines born from these intersections challenge notions of cultural purity and reveal a more intricate and localized history of American food culture. Immigrant communities, facing economic hardship, often blended their own traditions with local, inexpensive food sources, creating unique culinary expressions that complicate simplistic binaries of “civilized” versus “barbaric.”

Accusations of eating unusual animals towards migrants meanwhile in the U.S. animals as possums, raccoons, groundhogs, turtles, squirrels, or rats are part of the local cuisine and consumed without fuss—creatures not commonly consumed in other cultures or considered taboo by immigrants—highlight the hypocrisy in American food discourse. While such practices are viewed with disdain by mainstream society, they are rooted in the survival tactics of marginalized communities, both immigrant and native. These traditions persist in local cultures, particularly in regions where economic survival outweighs conformity to cultural norms. Yet, they become stigmatized when associated with immigrant groups, reinforcing xenophobic narratives that mark these communities as other.

In a country that prides itself on individualism and diversity, American food culture remains dominated by the homogenization and standardization of fast food chains. Corporations like McDonald’s and Starbucks, shape the nation’s diet through highly industrialized, replicable, and mass-consumable food products, which obscure local and artisanal food traditions. [34] Even those chains that claim to offer customizable menus or artisanal options maintain a strict corporate structure that prioritizes efficiency, scalability, and profit over genuine culinary diversity. This industrial logic underscores a broader socio-economic pattern of reducing complexity in favor of mass production and food industrialization. [35]

This mass standardization reflects broader socio-economic forces that shape American consumer culture. [36] The proliferation of fast food chains, for example, reflects the capitalist demand for efficiency and predictability in both production and consumption. The drive for expansion, and the need to maintain a consistent brand image across regional and even global markets, prioritizes uniformity over uniqueness. Even as some chains present themselves as purveyors of ‘choice,’ offering slight variations at the counter, the underlying logic remains the same: a relentless pursuit of profit through scalability. Such scalability necessitates the eradication of the very cultural nuances that are celebrated in other, more traditional food cultures.

The pursuit of the American Dream has often been tied to food and as a journey towards abundance, [37] with the early waves of immigrants arriving on U.S. shores in search of a land of plenty. Having fled war, famine, and economic despair, they were lured by promises of abundance. Yet, the reality of life in America was and is far more challenging. Jobs were difficult to secure, and a vast body of literature documents the fierce competition between immigrant groups, each vying for lower wages to access employment. Historical accounts, such as those documented by Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives, reveal the fierce competition among immigrant groups for low-wage jobs in industries that capitalized on labor exploitation. [38] Irish, German, Chinese, and Italian immigrants in the 19th century fought for employment opportunities, often undercutting each other’s wages, while hoping to climb the economic ladder.

This historical pattern wasn’t limited to the 19th century. The Great Migration of African Americans to northern industrial cities during and after World War I saw a similar dynamic, where Black labor was often used as a counterbalance to white labor strikes, creating racial tensions that were as much about labor competition as racial animosity. In more recent decades, the Bracero Program (1942-1964), [39] which brought Mexican laborers into the United States to work on farms, exemplifies the government’s continued reliance on cheap labor to sustain the economic engine of its capitalistic regime.

The U.S. government’s constant search for cheap labor, while emphasizing technological innovation and the golden paved roads of the American Dream, is rooted in this history of wage suppression and has consistently relied on immigrant workers while denying them full legal and economic rights. Waves of immigrants have been forced to undercut each other and the locals, eating out each other’s access to jobs, and devouring each others’ possibility for successful social upwards mobility in the pursuit of the American Dream. The locals’ response has been characterized by identifying immigration and the very notion of multiculturalism as problems to address, as Peter Brimelow argues in Alien Nation, [40] instead of considering the underpinning framework of capitalist exploitation dogmatically supported by both political parties which imprisons migrants and locals in the straitjacket definition of deplorables.

In the agricultural sector, migrant laborers, particularly undocumented workers, continue to endure wage theft, unsafe working conditions, and the absence of healthcare or labor protections. [41] The Economic Policy Institute has shown that undocumented workers are disproportionately vulnerable to these abuses, reflecting a broader pattern of systemic exploitation in the American labor market. This reality contradicts the idealized vision of the American Dream, wherein hard work and perseverance are supposed to lead to economic success and upward mobility.

Meanwhile, the American workforce is increasingly trained to execute tasks rather than organize to protect its own interests. The decline of labor unions since the 1950s, along with a corresponding rise in precarious employment with laws and regulations that immigrants are unable to contest without proper legal and administrative support, [42] has reinforced this structure, ensuring that the American Dream remains attainable for only a select few. As scholars like Howard Zinn have argued in A People’s History of the United States, the real winners of the American Dream have always been the elite, while the rest are left as roadkill—victims of a system that thrives on disposability and exploitation. [43]

Image 6: Lanfranco Aceti, Even Staring into the Abyss Must Be Turned in an Opportunity, 2019. From the series Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

The trajectory of U.S. labor and immigrant history reveals a persistent drive toward creating a vast, uncritical, and underpaid workforce, masking the harsh realities of labor exploitation under the guise of opportunity. This veneer of the American Dream, propped up by narratives of individual success and economic growth, has long obscured the systemic inequalities that make it unattainable for the many who continue to seek it.

In the pursuit of the American Dream, the struggle for food survival takes on a deeply symbolic and material role. While mainstream discourse often ignores the economic inequalities embedded in the U.S. system, food becomes a reflection of broader socio-economic structures. Poverty within the U.S., particularly in marginalized and immigrant communities, is a pervasive issue, yet its complex histories and lived realities are rarely conveyed to local and, even less so, to global audiences. These histories include not only the economic deprivation but also the survivalist food practices that have evolved as a response to scarcity while abundance for the few is successfully paraded under the insignia of the American Dream to the benefit of the U.S. imperial strategies. [44]

The exhibition Jacob Riis: Revealing “How the Other Half Lives”, co-hosted by the Library of Congress and the Museum of the City of New York, presents a powerful visual and narrative record of the conditions facing impoverished New Yorkers in the late 19th century aspiring to achieve the American Dream. Among the highlighted works are Riis’s photographs from the winter of 1892, when he visited eleven of the city’s sixteen riverside dumps and documented the harrowing lives of children living and working amid the refuse. Riis wrote, “I found boys who ought to have been at school, picking bones and sorting rags… They said that they slept there, and as the men did, why should they not? It was their home. They were children of the dump, literally.” His observations expose the bleak normalcy of child labor and homelessness in this era, where young lives were consigned to survival in conditions unimaginable today. These were children to whom dietary choices were a foreign concept—sustenance came from what could be had, not selected.

If American cuisine pretends to have historically avoided the consumption of pets like cats and dogs—common in certain stereotypical narratives about immigrant food cultures—it nonetheless includes a wide array of processed and hunted food items that might be considered inedible or taboo in other cultures. From processed foods, laden with preservatives and fillers such as McDonald’s fare, to game such as possums, groundhogs, or even raccoons and rats in rural regions, these consumption practices reflect a history of making do with what is available.

The systemic issues in U.S. infrastructure further complicate this picture of scarcity. The lack of robust public transportation forces individuals to rely on private vehicles to access essential services. This reliance perpetuates a cycle where one’s ability to work, access healthcare, or even buy groceries is directly tied to the capacity to afford a car, fuel, and vehicle maintenance. For low-income communities, including many immigrant populations, this creates additional layers of vulnerability. [45] The American paradox emerges in full view: a country rich in resources and opportunity but riddled with structural barriers that leave many grappling with scarcity amidst supposed abundance.

This paradox is intricately connected to economic inequality. While the U.S. prides itself on being a land of opportunity, the capitalist framework has made wealth accumulation uneven, leading to a large section of the population struggling to make ends meet. For these individuals, the dream of prosperity becomes a distant ideal, overshadowed by the daily challenges of survival. Food, transportation, and housing [46] are not merely commodities but battlegrounds where the socio-economic disparities of American life are played out. [47]

This observation ties into a larger critique of U.S. economic policies, which prioritize privatization and individual responsibility over collective welfare. The minimal investment in public transportation infrastructure—compared to countries with stronger welfare systems—exemplifies the prioritization of the wealthy and the further marginalization of the poor and immigrant populations. These issues underscore the deeply entrenched inequities that persist in contemporary American society veiled with the omnipresent and hypocritical shroud of the American Dream. [48]

Detroit, known as the “Motor City,” offers one of the most visible examples of the devastating consequences of the collapse of U.S. industrial capitalism and of wage suppression between racially and ethnically diverse communities. [49] Once the hub of American automotive production, the city’s decline mirrors the larger story of industrial disinvestment. [50] The urban prairies that now stretch across much of Detroit are the desolate aftermath of bulldozing burned-out crack houses and abandoned buildings, leaving behind vacant lots where factories and homes once stood. These prairies symbolize the deterioration of the social and economic fabric that sustained the city during its industrial heyday, the attempts and efforts to renaissance, [51] and the aesthetization of poverty and wasteland. [52]

Efforts to cultivate community gardens and vegetable plots in these spaces, while symbolically powerful, remain insufficient to generate a sustainable, organized movement for food security. Growing one’s own food requires both a stable workforce and financial resources—two commodities that communities ravaged by economic hardship, drug addiction, and social neglect do not possess. For many in Detroit [53] have shown that while these initiatives build community resilience, they lack the capacity to provide the necessary scale for long-term self-sufficiency.

The collapse of Detroit’s industrial base was paralleled by a rapid influx of drugs in the 1980s, contributing to rising rates of alcoholism, depression, and social decay. This multifaceted crisis has left local populations with little to offer immigrants who arrive seeking opportunity, only to find that they represent yet another layer of competition for already dwindling resources. As sociologists like Loïc Wacquant argue, these communities, decimated by deindustrialization and state neglect, perceive immigrants not as fellow victims of neoliberal capitalism but as additional threats to their already precarious existence of belonging and citizenship within a state with clear-cut class and racial social divides. [54]

The consequences of this collapse are not isolated to Detroit. Cities across the Rust Belt and beyond, such as Flint, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana, exhibit similar dynamics: declining job opportunities, crumbling infrastructure, and a populace struggling to adapt in an era of austerity and economic instability. The inability of these cities to support new waves of immigrants underscores the broader failures of U.S. economic policies, which continue to prioritize corporate profit over the well-being of vulnerable populations, both local and immigrant.

The use of non-traditional animals like possums, raccoons, squirrels, and rats in American cuisine is far from new, though it rarely surfaces in mainstream media or popular cooking shows, at home or abroad. Such practices, long a part of American food culture, particularly in rural and impoverished areas, have been essential for survival, dating back to times of economic hardship such as the Great Depression or the or the days of the pioneers. During these periods, and even into the present in regions affected by poverty, the hunting and consumption of “critters” [55] became and is a pragmatic necessity rather than a culinary choice. However, these practices remain largely excluded from the narratives that dominate mainstream cooking shows and food networks, which focus on luxury and abundance and not on economic deprivation and rat-soup for dinnertime.

While the media continues to portray an aspirational lifestyle, characterized by gourmet meals and culinary diversity, these depictions are often reserved for the privileged few. These are the privileged few who fear being devoured by those who themselves have pushed at the margins by cannibalizing their opportunities and possibilities for a better life. [56] It is a vicious circle of eating and being eaten, within which from the Native populations who were ghettoized in reserves to contemporary poors (enslaved or migrants) ghettoized in the definitions of deplorables, everyone is waiting for the opportunity to devour the other. [57] Americans still fear the primordial fear of the unknown of the first colonial settlements, since they are still people of a frontier and who could disappear and… never be heard from them again. [58] It is in this context that for much of the population, food insecurity remains a stark reality. The rise of the “working poor”—a new phenomenon in which individuals hold multiple jobs but still cannot achieve financial stability—demonstrates how the American dream is inaccessible to many. These individuals, particularly in rural areas, often have little choice but to rely on cheaper processed foods and more unconventional food sources.

This socio-economic disparity highlights the growing chasm between those who can participate in the gourmet culture showcased on TV and those who must resort to survival tactics that involve roadkill and foraging. The media’s depiction of culinary life, much like its portrayal of the American Dream, is often a sanitized version of reality, disconnected from the experiences of the working poor and the mass production of food for lower-end consumers. [59]

In the end migrants and locals are obliged to face up to the realities and contradictions of the American dream. “When you’re in Haiti and you think about going to the U.S., you don’t think that you’d ever be treated this way,” Jean-Baptiste said. “It’s such an awful feeling for people who thought that being in the U.S. was the best thing that could ever happen to them.” [60]

Am I What I Eat? Plucking and Skinning the American Dream

“I hated this country… and if I had a choice, I would have never left. They told us that the roads were paved with gold, but I haven’t seen any gold anywhere, despite all the hard work.” These are the unrecorded words of an Italian woman who migrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s. “When the Depression hit, and the men were without jobs, I ended up plucking songbirds. At night, the men would go into the fields and throw nets, risking being shot, just to catch these birds. The saddest part was that one of them could die for a bunch of stupid little birds. Do you know how long it takes to pluck the feathers out one of those little things? You have to be firm with your fingers but not too forceful, so the feathers don’t rip the meat from the bone. They’re small and scrawny, with very little meat… I spent entire nights doing that. I hated it. There were no jobs and no money… and so I did it.”

She continued, “One day, I placed a small dish of milk outside the kitchen door. I had already pawned the earrings I brought from Italy—they were part of my dowry. It didn’t take long for two cats to show up. Three nights later, after skinning them and letting the meat ‘spurgare’ (cleanse) in the snow, we had something to eat. It was my grandmother’s recipe that she taught me. I had hidden the cats in the snow, and spent the night awake, constantly checking to make sure no one would steal them. I didn’t eat it myself, but nobody asked what it was. They must have assumed it was rabbit, I suppose. They didn’t ask, and I didn’t tell.”

It took three generations for the family to attain middle-class status by the 1990s, culminating in an American fourth generation child who could be fully considered part of the middle class.

In Italy, the practice of consuming cat meat has historical roots as part of regional culinary traditions. While no longer widely practiced—and certainly not openly—this tradition persists as a cultural memory, like a recipe of black bird breast meat pie in the U.S. [61] Legally, the consumption of cat meat is not explicitly prohibited by Italian law, although there have been attempts to formalize such a ban. [62] These efforts, however, have failed to pass through parliament, leaving the practice indirectly discouraged, criminalized, and punished by animal welfare laws but not outrightly forbidden.

Would Italians have resorted to eating cats in the U.S. if faced with dire circumstances? Most likely, yes. Like other immigrant groups, Italian immigrants brought their cultural traditions and survival strategies with them. In the face of extreme poverty or food scarcity in the U.S., they would have likely turned to familiar practices for sustenance, including eating cats if necessary. However, due to the social stigma surrounding this practice in the U.S., such actions would have been discreet and certainly not publicly acknowledged.

One particularly vivid example of the cultural clash experienced by immigrants during the Prohibition era can be seen in the story of an Italian immigrant family in Queens, New York. Italians, who traditionally drink a small glass of wine with meals, found themselves at odds with American laws during Prohibition, which criminalized alcohol consumption. The elderly son of one such immigrant shared how his father, who had a few grapevines in his backyard to produce small quantities of wine for personal consumption, was arrested after a neighbor reported him to the police. The sight of a man sipping wine under the shade of his pergola became grounds for legal action, leading to his arrest. From that day until his death, the father drank his wine in a small tin cup, hidden from view, a poignant reminder of how even the most intimate cultural practices could be policed and suppressed. This shift from open enjoyment to secrecy illustrates the larger theme of immigrant communities having to conceal aspects of their identity to avoid persecution or legal consequences.

This narrative speaks to the broader issue of how immigrant communities navigate cultural identity in the face of legal and social pressures. The story is emblematic of a wider pattern in which immigrant groups, particularly those arriving in large numbers in the early 20th century, faced pressure to conform to the dominant American cultural norms. This process of forced adaptation is not just about legal obedience but involves the erasure or suppression of deeply embedded cultural practices, from culinary traditions to religious observances. As in the case of this Italian family, everyday activities, such as enjoying wine with lunch, were criminalized, making the act of preserving one’s cultural heritage an act of defiance.

This incident also highlights the role of social surveillance in immigrant life. Neighbors, often from different ethnic or social backgrounds, could act as enforcers of conformity, reporting perceived violations of the law, as happened here, and how it is increasingly happening now through social media, which, are used as tools of a moralistic decontextualized enforcement of customs and laws. This reflects how immigrant communities were not and are not just shaped by the law but by the broader societal expectations that seek to regulate their behavior and assimilate them into a narrowly defined version of American life. It also hints at the dynamics of exclusion, where immigrant customs were and continue to be framed as foreign or even criminal.

The story of the Italian immigrant in Queens who quietly shifted from drinking wine out of a glass to a tin cup after being arrested for violating Prohibition laws encapsulates the tension between immigrant traditions and the imposition of legal and cultural conformity. Italian families, accustomed to a small glass of wine during meals—a deeply rooted cultural practice—found themselves criminalized by U.S. Prohibition policies. This event speaks to the broader theme of cultural policing, where immigrant communities are pressured to erase or hide their heritage to assimilate into a society that paradoxically celebrates individual freedom while suppressing cultural difference.

“Still eating spaghetti, not yet Americanized.” [63] was the comment of a social worker reported by Erik Amfitheatrof in his book The Children of Columbus. This points out to a high level of surveillance and self-surveillance.

The act of self-surveillance, hiding one’s cultural practices to avoid legal repercussions, mirrors larger systemic forces that have historically shaped the immigrant experience in the U.S. From the late 19th century through the 20th, immigrant groups were often forced into a process of “whitening” or cultural sanitization to avoid marginalization, as described by historian David Roediger in his analysis of the racialization of European immigrants. [64] The simple act of consuming wine, re-contextualized by Prohibition, became a marker of social deviance, turning a cultural norm into a criminal act. This shift reflects what Michel Foucault describes as the internalization of the “panoptic gaze,” [65] where power is enacted through a state of constant surveillance, pushing individuals to modify their behaviors without direct intervention.

If some individuals may have consumed in Springfield, or elsewhere, dog, cat, or goose meat out of necessity, cultural habit or preference, they would have been highly unlikely to make a public spectacle of it, given the negative perceptions and potential stigma and consequences in the U.S., where social media play a social surveillance role.

Before provoking a hypocritical reaction from my Anglo-Saxon audience, it might be prudent to explore the history and lesser-known culinary traditions that have shaped the so-called “land of the American Dream.” Food production, preparation, and preservation are deeply intertwined with the rhythms of seasons, the passage of time, and the sheer effort required for survival. The sanitized supermarket version of food—offering choices between organic or grass-fed, skinless chicken breasts, butchered by low-wage immigrant workers—is a far cry from the true complexity of food life on a farm. Those who have lived through it, not just visited for a few weeks as tourists, understand that it entails far more than choosing between convenience foods; it involves the messy, hands-on processes of raising, killing, and butchering animals. Vegetable growing is as complex and arduous. Vegetables need time to grow and are not instantly available. The eating process is faster and cheaper only if one resorts to foraging, stealing someone else’s produce, or picking up road kills. [66]

Image 7: Lanfranco Aceti, I’m a Celebrity…Get Me Out of Here!, 2019. From the series Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

Yet, in today’s society, especially among the higher middle class in the U.S., we see a moral dissonance caused by the distancing between food production and consumption: animals, particularly pets, have become more valued than the lives of poor people. While a pet’s death might provoke an outpouring of emotion, the death of a poor person often elicits indifference. This warped moral outlook and untenable ethical stance underscores a deep cultural malaise—one where the lives of vulnerable people are deemed expendable, overshadowed by the sentimental importance placed on animals.

This critique is not about disparaging pets or denying animal rights, but about challenging the contradictions that lie at the heart of contemporary American culture, and consequentially even in Europe, where socioeconomic inequality has rendered certain lives invisible while elevating others to an untouchable status. The historical context of food production reminds us that survival often trumps sentimentality, and in societies experiencing extreme deprivation, moral choices are not as simple as they appear from a position of privilege.

It is for this reason that I find both the politically explosive outrage and the blanket defense of immigrants appalling. The inability to understand their motives—whether dismissing them as “savages” or assuming that certain animals like geese, dogs, or cats (not to mention raccoons, armadillos, squirrels, and rats—staples of some regional American cuisines) have never been consumed—is a stance both culturally racist and woefully ignorant. Such reactions, particularly when they attempt to conceal the underlying poverty caused by social or personal struggles, completely overlook the class factors that drive these behaviors.

In this context, what is truly offensive is not the act of consuming taboo animals, but the unwillingness to confront the brutal realities of poverty. Both the knee-jerk condemnation and oversimplified defense of immigrants ignore the fact that their choices are often dictated by survival, not personal preference or culture. Poverty forces hard decisions, and the moral judgment of those who have never faced such conditions is both ignorant and deeply rooted in privilege. The real issue isn’t who ate what—it’s about acknowledging the harsh conditions that lead to those choices in the first place.

The video I chose of a man from the Ivory Coast, filmed near a train station in Italy, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-20B08OEjrQ, captures a scene that is both arresting and emblematic of the stark divisions in global cultural responses to survival. It reminds me of Riis’s photographs, without the pornographic aestheticization of poverty, and it evokes a challenge to the hypocrisy of the sanitized and glossy representation of American film and media narratives. What is most arresting about the scenes in the video, however, is not the gruesome act of roasting a cat by necessity but rather the intense moral outrage expressed by a bystander, a woman who indignantly screams that cats are not eaten in Italy, where they are viewed as family members, akin to children. Her reaction epitomizes a kind of moral absolutism that transcends national borders, a perspective shaped by cultural imperialism which equates certain taboos about animals with universal ethical standards. It is the same decontextualized moralism that informs the political outrage of the right and of the left in America.

The video vividly exposes a deeper hypocrisy embedded in modern, affluent societies, where the cultural memory of survival by any means necessary has been repressed or conveniently forgotten. In Italy’s own history—particularly during times of war and extreme deprivation—it is well documented that people resorted to eating cats, among other taboo animals, to survive. Yet, in this moment, the woman’s moral indignation reveals an inability to empathize with the man’s circumstances, as well as an alarming ignorance of her own cultural history. In the comments accompanying the video, several individuals remark on the likelihood that her own family, during World War II or earlier periods of hardship, may have partaken in the very practice she now condemns. This dissonance speaks to a broader cultural amnesia and a failure to grasp the realities of survival when confronted with hunger.

In these interactions are at play the broader dynamics of cultural imperialism, wherein certain moral and cultural standards—particularly those surrounding the treatment of animals—are not only privileged but are also exported globally as normative. In the U.S., where the commodification of pets and the prioritization of their well-being often supersedes that of marginalized human communities, this phenomenon has reached its zenith. Scholar Chris Hedges describes this dynamic as part of a larger imperial culture that prioritizes consumerism and sentimentality over the stark realities faced by the impoverished, both domestically and abroad. [67] The Italian woman’s reaction is not isolated but reflects the global exportation of this moral framework, one that divorces itself from the harsh realities of survival in favor of a sanitized, consumer-driven ideal of what life—and indeed, death—should look like.

This incident demands a critical reflection on the socio-economic conditions that force individuals into acts that many in wealthier societies would view as barbaric or uncivilized. The assumption that certain animals are inherently sacred or untouchable reflects not just a cultural bias but also a profound ignorance of the socio-economic pressures that shape behavior. The man from the Ivory Coast, driven by hunger, did not have the luxury of choosing between ethically sourced, grass-fed meat options at a supermarket like Whole Foods spending his Whole Paycheck. [68] Instead, his act was one of sheer necessity, borne out of a struggle that affluent societies are increasingly unable—or unwilling—to comprehend.

Furthermore, this moment highlights a disturbing trend in contemporary society: the elevation of pets to the status of children, coupled with a corresponding devaluation of the lives of the poor and disenfranchised. In both Italy and the U.S., the cultural narrative surrounding pets has evolved into one where their well-being is often placed above that of human beings in need. This phenomenon can be understood as part of a broader cultural malaise, where consumerist values intersect with moralistic outrage, leaving little room for the empathy or understanding required to address the root causes of poverty and hunger.

The Italian woman’s reaction is not merely a personal expression of outrage; it is symptomatic of a larger societal failure to engage with the complexities of food security, poverty, class divisions, and cultural survival strategies. Rather than confronting the man’s desperate need for food, she resorts to moral condemnation and the threat of arrest, thereby reinforcing the very structures of inequality and ignorance that perpetuate such crises. As the video’s commentators astutely observed, the woman’s family likely engaged in similar practices during times of scarcity, revealing the extent to which cultural memory has been erased or suppressed in favor of an idealized—and ultimately hypocritical—moral stance. We are presented, yet again, with the violence of cultural arrogance that dismisses the survival tactics of the impoverished as barbaric or primitive.

In sum, this video serves as a powerful reminder of the deep chasms that exist between those who can afford to maintain moral absolutes and those who must confront the brutal realities of survival. It challenges us to rethink the ways in which we engage with cultural differences, especially when they intersect with issues of poverty, hunger, and necessity. Rather than reacting with moralistic outrage, societies must strive to develop a more nuanced understanding of the socio-economic forces that shape behavior, particularly in times of crisis.

In the media coverage of the Trump vs. Harris debate, the focus on the claim that “they are eating the dogs” and “they are eating the cats” demonstrates a symptomatic failure of mainstream journalism to address the core issue of migrant hardship and the devouring and cannibalizing nature of American culture towards migrants, towards its poor, and towards the existential fears of the middle class in a state of constant job insecurity and precarity. [69] It is the representation—yet again—of a non-debate, where the celebration of vacuousness has a clear goal: eliminate any hint of class differentiation within the framework of the American Dream between two parties that want to keep in shackles the working and middle class independently of gender, religion, race, and class. [70] Rather than engaging with the underlying socio-economic realities and class conflicts that might have compelled immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, to resort to extreme survival tactics, the media’s immediate priority was to “debunk” the claim. This reductive approach bypasses the urgent questions of what conditions in America might drive such actions and the implications for those forced into desperate measures.

Image 8: Lanfranco Aceti, I Bled Out for the American Dream, 2019. From the series Pets or Meat. Photographic print on fine art paper. Dimensions: variable.

The media’s reflexive debunking prioritized an ideological agenda over the very real struggles of both the immigrant population and the local communities that have been required to bear the brunt of a constantly failing and flailing American Dream. This theatrical response reflects the broader political polarization that has gripped U.S. discourse. [71] Instead of acknowledging that these localities are under-resourced and strained in their efforts to assist migrants, the media opted to perpetuate a binary, oversimplified narrative of victimization, one that ultimately does a disservice to all involved. Moreover, the media’s self-legitimization through fact-checking reveals a more insidious mechanism. [72] While ostensibly presented as a commitment to objectivity, this practice often functions as a superficial display of authority, suggesting that by verifying isolated facts, outlets automatically assume the mantle of truth. Yet, the verification of a single fact—such as the absence of confirmed reports of pet consumption—does not equate to a comprehensive understanding of the issue, nor does it address the broader context in which these incidents are situated. [73]

This media-driven defense did not advocate for immigrants’ human needs or engage with the tangible realities of their precarious situations. Rather, it constructed a defense of ideology—specifically, a romanticized portrayal of the migrant as a version of Rousseau’s noble savage, a figure stripped of the messiness of real human suffering in favor of an idealized representation that suits the political sensibilities of a certain bourgeois left and American middle class. [74] In this sanitized depiction, the immigrant is presented as a passive, virtuous figure who exists in contrast to the more complicated, morally compromised reality of poverty and survival strategies. Such representations reduce the immigrant experience to a rhetorical tool, wielded in service of ideological goals rather than a genuine commitment to understanding or alleviating the underlying suffering. The immigrants and the local poor are used, once more, to support the ideological stances that prop up the crumbling illusions of the American Dream. [75]

The appropriation of Rousseau’s ideas to construct this contemporary image of the noble savage ignores the historical complexities surrounding both migration and local economies. In so doing, the media fails to offer a balanced or informed narrative that includes the struggles of native populations, who often face resource depletion and strained infrastructure in their efforts to support migrant communities. [76] These realities are obscured by the fixation on debunking symbolic issues like pet consumption—issues that serve more to inflame public outrage than to spark meaningful conversations about economic disparity, resource allocation, and social integration. The complexity of social integration, in particular, is a burden shifted often onto the goodwill of locals when instead should be a collective social endeavor and a federal policy priority.

By presenting the situation in Springfield as one of ideological contestation rather than as a multifaceted humanitarian crisis, the media not only diminishes the plight of immigrants but also overlooks the legitimate concerns of local citizens. The result is a debate that traffics in spectacle rather than substance, diverting attention from the systemic failures that create such untenable conditions for all parties involved. It is the media’s inability to “break through the screen of often absurd, sometimes odious projections, that mask the malaise or suffering as much as they express it.” [77]

In sum, the debate around whether or not immigrants were eating pets is a useful political distraction from the more pressing conversation about how both immigrants and local communities are being left to struggle in conditions of deprivation. The focus should not be on defending a sanitized ideological representation of migration, but on addressing the realities of hunger, poverty, and the inadequate support systems that have left entire communities—both immigrant and native—vulnerable and under-resourced.

The under-resourced communities of Middle America, emblematic of a broader national crisis, are starkly represented by the video from Canton, Ohio, depicting a Black American woman consuming a raw cat. [78] This woman, neither of Haitian descent nor a Springfield resident, was clearly in a state of crisis and not fully cognizant (compos mentis). In parallel, the Ivory Coast man in Italy he was videoed while roasting a cat. Though the circumstances differ, both individuals represent the alarming reality of impoverished people committing unusual acts or resorting to extreme measures to survive. In both cases, the state response—arrest and police intervention—was inadequate and unwarranted. What they needed, instead of criminalization, was sustained care through comprehensive social services. [79]

This scenario reveals the deep structural deficiencies in social support systems, both in the U.S. and Italy. These individuals, living on the margins of society, exemplify the abandonment of the poor by the state and society alike, left to endure crises without adequate assistance. The lack of accessible mental health care, homelessness support, and poverty alleviation programs has created conditions where individuals in desperation turn to acts seen as deviant or incomprehensible by mainstream society. Yet, instead of receiving the support they need, they are often further marginalized by law enforcement and social stigmatization. [80]

The deeper issue here extends beyond the immediate horrors of poverty—it lies in the collapse of the welfare state, which should have been designed to protect the most vulnerable. This collapse, driven by decades of violent and unchecked neoliberal policies, started during the Reagan and Thatcher years, has resulted in the systematic impoverishment and marginalization of entire communities. [81] Capitalist plundering, prioritizing profit over social welfare, has not only destroyed safety nets but has also shifted the burden onto individuals. Those now trapped in dismantled, degraded communities are often made to feel as if their poverty is a personal failure, rather than the outcome of political decisions that gutted public resources and created ghettoized zones of deprivation.

This analysis highlights how the erosion of social support structures coincides with the entrenchment of inequalities and the privatization of welfare responsibilities. The result is a societal narrative that blames the impoverished for their own circumstances, despite the systemic failures of governance and the ongoing legacies of wealth extraction that have rendered entire populations vulnerable.

The treatment of the poor in times of crisis follows a familiar and troubling historical pattern: stigmatization, dehumanization, and scapegoating. [82] This phenomenon has persisted through various periods of economic and social distress, [83] most visibly during wars when populations, deprived of food, resorted to consuming animals like cats, which are typically viewed as companions rather than sustenance. [84] The American public’s reaction—shock and dismay at such acts—reveals a deep-seated hypocrisy. [85] People today express horror at the idea of eating animals culturally regarded as domestic, forgetting that under severe deprivation, civilization’s veneer quickly erodes. What’s more, this response exposes a fear not just of physical starvation but of a symbolic invasion—a devouring of the middle class, a coming to pass of the invaders who ate the Natives and are now facing the danger of being eaten out themselves by new waves of invaders. The consumption of domestic animals metaphorically represents the encroachment on their domestic life and security and the devouring of their American Dream. This fear plays into broader cultural anxieties about survival, assimilation, and identity during crises, where the very fabric of society seems vulnerable.

This historical amnesia demonstrates the fragility of modern life, where food security is taken for granted, and the collective shock at these survival strategies reflects the thin boundary that separates stability from catastrophe. The line between civilization and desperation is not as solid as we might imagine, and in moments of crisis, those societal boundaries can easily crumble.

This detachment from the past—both in terms of survival skills and social solidarity—reflects a broader moral and ethical failing in the way modern societies understand poverty, need, and human dignity. The Canton, Springfield, Campiglia Marittima, and Palermo cases are not just isolated events of deviance or lack of deviance; they are symptomatic of larger societal failings, where the impoverished are criminalized instead of cared for, and where the public outcry over animal consumption serves to mask deeper, more uncomfortable truths about the abandonment of the poor and an existential condition that more of assimilation into a multicultural or racialized idea of the American Dream speaks of cannibalization of identities and lives.

In addressing these issues, we must not only advocate for more comprehensive social services but also for a broader cultural shift—one that resists the urge to stigmatize or hide the survival strategies of the poor and instead asks how society can collectively ensure that no one is forced to make such desperate choices.

This section will close with a particular story of the disappearance of geese and ducks, not in Springfield, Ohio, but in Ilford, England. [86] We must situate the anecdote of an immigrant boy attempting to take a duck from a pond to feed his terminally ill mother within a broader analysis of food traditions, animal welfare, and socioeconomic disparities. This particular event, which took place in the UK, highlights the cultural and legal complexities surrounding food sourcing in Western societies. The boy, of Afghan origin, sought to catch a duck from a public pond, driven by desperation to alleviate his mother’s suffering, believing in the curative properties of duck meat a priest from his country had told him, even though such beliefs might not hold scientific validity.

In the UK and across much of the Western world, the regulation of hunting, fishing, and foraging has transformed significantly over time. What was once a necessary skill for survival is now highly regulated, with laws protecting both public and private resources. The enforcement of these regulations has, in many ways, mirrored the old poaching laws of feudal Europe, when access to hunting was restricted to land-owning elites, effectively criminalizing the subsistence activities of the poor. [87] Today, these laws, though framed under the banner of animal welfare and environmental conservation, often ignore the plight of individuals and families struggling with food insecurity.

The case of this young Afghan boy illustrates a clash between deeply held food traditions and the Western legal framework. For many communities, especially those from rural or war-torn regions, the line between public and private resources is blurred. In the boy’s eyes, the duck in the pond was not an aesthetic or environmental entity but a means of survival. His actions underscore the desperate conditions that some immigrants face in host countries, and how the rigid application of Western regulations further marginalizes them. “Parks Constable (PC) Iqbal Sheryar, who speaks fluent Urdu, met with an angry response when he told the boy to buy a bird from a nearby branch of Sainsbury’s instead.This young guy was really upset when we told him he couldn’t take a duck from the pond, and begged us to let him jump in and grab one.”

It is difficult to blame this boy for his attempt to provide for his dying mother. While there is no evidence to support the medicinal properties of duck meat, this episode reveals the need for a profound human empathy that transcends borders and laws. The harsh enforcement of animal welfare regulations, in this case, fails to acknowledge the underlying human suffering. This incident serves as a reminder of the growing alienation between agricultural life, survival skills, and modern society’s priorities.

As societies in the Western world become more removed from subsistence-based living and agrarian religious and cultural customs, empathy for those who still rely on such practices diminishes. The story of this boy illuminates the broader issue of how sanctimonious imperialism—rooted in the commodification of life, particularly of the poor when compared to the lives of the animals of the rich—fails to provide space for nuanced considerations of poverty, migration, and survival. In Russeauian terms, the idealized perception of migrants is at fault as much as their demonization: “The conclusion of the Discourse favours not this purely abstract being, but a state of savagery intermediate between the ‘natural’ and the ‘social’ conditions, in which men may preserve the simplicity and the advantages of nature and at the same time secure the rude comforts and assurances of early society.” [88] Nevertheless, in this new world order, where food has become even more of a privilege than ever was rather than a right, the desperate attempts of the poor to preserve their lives are criminalized rather than understood or addressed.